History

Although the Leishmania species differ clinically and biologically, their characteristics overlap and each clinical syndrome can be produced by multiple species of Leishmania. [2, 3, 1]

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

The broad spectrum of clinical manifestations of cutaneous leishmaniasis often is compared with that of leprosy. Cutaneous leishmaniasis can be simple or diffuse (disseminated). Different species, as well as host factors, can also affect the clinical picture, in which some species cause "wet" ulcers and others "dry" ulcers.

The hallmark of cutaneous leishmaniasis is skin lesions, which can spontaneously heal in 2-10 months. Inoculation occurs after a sandfly bites an exposed part of the body (usually the legs, arms, neck, or face). Incubation occurs over weeks to months, followed by the appearance of an erythematous papule, which can evolve into a plaque or ulcer. These lesions usually are painless.

No systemic symptoms are evident. After recovery or successful treatment, cutaneous leishmaniasis induces immunity to reinfection by the species of Leishmania that caused the disease.

Localized cutaneous disease

Both New World and Old World species cause localized cutaneous leishmaniasis. New World disease usually presents with a solitary nodule, whereas Old World disease is associated with multiple lesions. Systemic symptoms are absent. Wound progression occurs over time and may exhibit localized lymphangitic spread.

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the right arm of the same soldier stationed in Kuwait. This 2-cm by 3-cm lesion was located at the exposed area where the sleeve ended. Note the satellite lesions.

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the right arm of the same soldier stationed in Kuwait. This 2-cm by 3-cm lesion was located at the exposed area where the sleeve ended. Note the satellite lesions.

The lesions usually are without pain or pruritus, although secondary bacterial infection may complicate the wound (see the following image). Healing may occur spontaneously over 2-12 months and is followed by scarring and changes in pigmentation. New World disease may progress to mucocutaneous leishmaniasis.

Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis

Diffuse cutaneous disease develops in an anergic host with poor immune response. This condition is associated with a deficient cell-mediated immunity that enables the parasite to disseminate in the subcutaneous tissues and has been reported in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

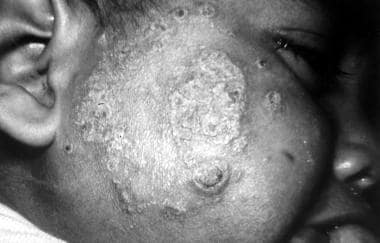

Infection is characterized by a primary lesion, which slowly spreads to involve multiple areas of the skin (face, ears, extremities, buttocks) until the whole body is affected. Plaques, ulcers, and nodules may form over the entire body, resembling lepromatous leprosy (see the image below). However, no neurologic or systemic invasion is involved; as a result, although the lesions are neither destructive nor erosive, they are disfiguring. The infections are chronic and may recur after treatment.

Although diffuse disease is more common with New World species in Central and South America, Old World L aethiopica may progress to diffuse disease in East Africa.

Diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Jacinto Convit, National Institute of Dermatology in Caracas, Venezuela.

Diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Jacinto Convit, National Institute of Dermatology in Caracas, Venezuela.

Leishmaniasis recidivans

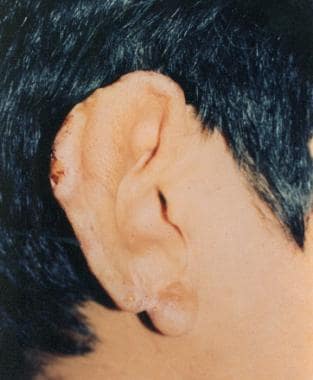

Leishmaniasis recidivans may occur years after a localized cutaneous lesion has healed, commonly presenting on the face (see the following image). New ulcers and papules form over the edge of the old scar and proceed inward to form a psoriasiform lesion. Infection may be from reactivation of dormant parasites or new infection from a different species. Skin trauma can result in activation of seemingly latent cutaneous infection long after the initial bite. The infections tend to be resistant to treatment.

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis follows the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis and has predominantly been described in Africa (about 2% of cases) and India (about 10% of cases).

The Indian variant occurs in patients 1-2 years and as long as 20 years after recovery from visceral leishmaniasis. This condition is characterized by multiple, hypopigmented, erythematous macules. Over time, these macules can transform into large nontender plaques and nodules that involve the face and trunk (see the image below). The disease resembles lepromatous leprosy and requires intensive therapy. The African variant occurs shortly after treatment of visceral leishmaniasis and is characterized by an erythematous papular rash on the face, buttocks, and extremities. These lesions spontaneously resolve over the course of several months.

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Courtesy of R. E. Kuntz and R. H. Watten, Naval Medical Research Unit, Taipei, Taiwan.

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Courtesy of R. E. Kuntz and R. H. Watten, Naval Medical Research Unit, Taipei, Taiwan.

In Sudan, patients often present with a facial rash consisting of small papules resembling measles that spreads to involve other parts of the body. This syndrome may heal spontaneously, but relapse is common. Established disease is generally difficult to treat.

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis that is resistant to antimonial agents has been reported, with an incidence rate of 1 in 700 cases.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Mucocutaneous disease, also called espundia in South America, usually develops by metastasis from disseminated protozoa rather than by local spread. This condition is most commonly caused by New World species, although Old World L aethiopica also has been reported to cause this syndrome. Secondary infection plays a prominent role in the size and persistence of ulcers.

Infection by L (Viannia) braziliensis may lead to mucosal involvement in up to 10% of infections, depending on the region in which it was acquired. The incubation period is from 1 to 3 months. The initial infection is characterized by a persistent cutaneous lesion that eventually heals, although as many as 30% of patients report no prior evidence of leishmaniasis.

Ulcer progression is slow and steady. Several years later, oral and respiratory mucosal involvement occurs, causing inflammation and mutilation of the nose, mouth, oropharynx, and trachea (see the following image), resulting in symptoms of nasal obstruction and bleeding. These can become sites of infection, sometimes leading to sepsis. Cases in which the time between the primary lesion and the appearance of mucosal involvement is up to 2 decades have been reported.

Progressive mucocutaneous disease is difficult to treat and often recurs. With prolonged infection, death occurs from respiratory compromise and malnutrition. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis may arise after inadequate treatment of certain Leishmania species.

Children rarely are affected.

Visceral leishmaniasis

Visceral disease, the most devastating and fatal form of leishmaniasis, is classically known as kala-azar or the Indian name for “black fever/disease,” which is a reference to the characteristic darkening of the skin that is seen in patients with this condition. Other terms used to describe visceral disease include Dumdum fever, Assam fever, and infantile splenomegaly in various parts of the world.

This condition occurs with both New and Old World species and results from systemic infection of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. The spectrum of illness ranges from asymptomatic infection or self-resolving disease to fulminant, severe, life-threatening infection; many subclinical cases occur and go unrecognized for each clinically recognized case.

The syndrome is characterized by the pentad of fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and hypergammaglobulinemia. The fever is continuous or remittent and becomes intermittent at a later stage. It is also characteristically described as a double rise in 24 hours, in which waves of pyrexia may be followed by a period without fever. Patients may also report night sweats, weakness, diarrhea, malaise, and anorexia. Melanocyte stimulation and xerosis can occur, causing characteristic skin hyperpigmentation.

Onset of visceral disease can be insidious or sudden. The incubation period varies after infection (usually 3-6 mo, but can be months or years) and may depend on the patient's age and immune status as well as the species of Leishmania. Young malnourished children are most susceptible to developing progressive infection; those who present later in the course of the disease may present with edema caused by hypoalbuminemia, hemorrhage caused by thrombocytopenia, or growth failure caused by features of chronic infection.

If visceral disease is left untreated, death frequently occurs within 2 years which may be due to hemorrhage (secondary to infiltration of the hematopoietic system), severe anemia, immunosuppression, and/or secondary infections.

A variant of visceral leishmaniasis has been described in US soldiers who participated in the Gulf War. This is associated with light parasitic burden and mild symptoms including fever, malaise, and nausea. A solitary case of Viseral leishmaniais presenting as autoimmune hepatitis was recently reported. [14]

Viscerotropic leishmaniasis

Viscerotropic leishmaniasis has an indolent but distinct clinical presentation and does not appear to progress to full visceral leishmaniasis. Patients have presented with an array of symptoms months to years after infection, including fever, rigors, fatigue, malaise, nonproductive cough, intermittent diarrhea, headache, arthralgias, myalgias, nausea, adenopathy, transient hepatosplenomegaly, and abdominal pain.

Although L tropica traditionally has been associated with cutaneous leishmaniasis, several reports of visceral disease have been reported from Kenya, India, and Israel. In addition, reports of patients returning from the Middle East showed presentations ranged from 1 month to 2 years after exposure, with many symptoms described above: malaise, fatigue, intermittent fever, cough, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Physical Examination

Cutaneous leishmaniasis

Cutaneous disease may have the following physical manifestations [2, 3, 1] :

-

Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis: Crusted papules or ulcers on exposed skin; lesions may be associated with sporotrichotic spread

-

Diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous leishmaniasis: Multiple, widespread nontender, nonulcerating cutaneous papules and nodules; analogous to lepromatous leprosy lesions

-

Leishmaniasis recidivans: Presents as a recurrence of lesions at the site of apparently healed disease years after the original infection, typically on the face and often involving the cheek; manifests as an enlarging papule, plaque, or coalescence of papules that heals with central scarring (ie, lesions in the center or periphery of an old healed leishmaniasis scar); relentless expansion at the periphery may cause significant facial destruction similar to the lupus vulgaris variant of cutaneous tuberculosis

-

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: Develops months to years after the patient's recovery from visceral leishmaniasis, with cutaneous lesions ranging from hypopigmented macules to erythematous papules and from nodules to plaques; the lesions may be numerous and persist for decades

The presentation of cutaneous disease varies depending on the stage of disease, although it mainly occurs in 2 forms, (1) an oriental sore caused by L tropica and (2) American cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L brasiliensis. Lesions are usually found in exposed areas (eg, face, arms, legs). The skin lesion begins as a nontender, firm, red papule several centimeters in size at the site of the sandfly bite. In time, the lesion becomes darker, widens with central ulceration, serous crusting, and granuloma formation. The border often has a raised erythematous rim known as the volcano sign.

The lesions may be moist or open with seropurulent exudate, or the ulcers may be dry with a crusted scab and become fibrotic or hyperkeratotic with healing (after about 3-6 mo, leaving a raised border).

Healed cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

Healed cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

Urban cutaneous leishmaniasis, caused by a subspecies of L tropica, presents as a dry cutaneous ulcer on the face and has an urban distribution. The incubation period is approximately 2 months. It is common in Western India, North Africa, the Mediterranean region, and Middle East. A similar disease in Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala is known as the bay sore or chiclero ulcer. It is a chronic lesion that occurs at the site of a sand fly bite.

Rural cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by L tropica and has a rural distribution. Multiple moist cutaneous lesions appear on the extremities and are associated with marked local subcutaneous infiltration and regional lymphadenitis. Both lesions are common in Central Asia.

Other findings of cutaneous disease include eczematous, psoriasiform, varicelliform, and verrucous lesions. The area surrounding the primary lesion may exhibit lymphangitic spread with palpable cords and subcutaneous nodules. This is common in New World lesions caused by L (Viannia) braziliensis infections.

Regional adenopathy, subcutaneous nodules, and satellite lesions may be present. The lesions are usually painless and without pruritus. A generalized inflammatory reaction to migrating parasites may be present in the skin surrounding the sore. Overlying bacterial infection may complicate the natural history. Healing occurs over months to years, leaving a characteristic retracted hypopigmented scar. Untreated sores can leave depigmented retracted scars. Thus, although this form is often self-healing, it can create serious disability and permanent scars.

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

Atypical appearance of Leishmania major lesion with local spread beyond the borders of the primary lesion. Many of the lesions in cases from Iraq show an atypical appearance.

Atypical appearance of Leishmania major lesion with local spread beyond the borders of the primary lesion. Many of the lesions in cases from Iraq show an atypical appearance.

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis

Post–kala-azar dermal lesions are categorized into 3 types, as follows:

-

Depigmented macules: The earliest lesions; present on the trunk and extremities

-

Erythematous patches: Appear early in the course of disease; seen on the nose, cheeks, and chin, with a butterfly distribution; they are photosensitive and become prominent toward the middle of the day

-

Yellowish pink nodules: Appear mostly on the face and replace the earlier lesions; the absence of ulceration distinguishes these nodules from those of cutaneous leishmaniasis (oriental sore)

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis consists of the relentless destruction of the oropharynx and nose, resulting in extensive midfacial destruction.

The initial skin lesion with mucocutaneous disease is often notable for its prolonged healing time and large size. In most cases, a healed scar can be identified based on careful examination. Months to years after the initial infection, patients may have rhinorrhea, epistaxis, and nasal congestion.

The lesion commonly arises at the mucocutaneous junction around the nose and may spread inward, destroying tissues and leading to deformity that requires plastic surgery. The lesion heals with scarring, causing the typical tapir or camel nose.

Examination reveals the following features:

-

Excessive tissue obstructing the nares, septal granulation, and perforation; nose cartilage may be involved, giving rise to external changes known as parrot's beak or camel's nose

-

Possible presence of granulation, erosion, and ulceration of the palate, uvula, lips, pharynx, and larynx, with sparing of the bony structures; hoarseness may be a sign of laryngeal involvement

-

Gingivitis, periodontitis

-

Localized lymphadenopathy

-

Optical and genital mucosal involvement in severe cases

Death occurs from suffocation secondary to airway obstruction, respiratory infection, and aspiration pneumonia.

Visceral leishmaniasis

Visceral and viscerotropic disease may manifest with the following physical findings:

-

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar): Potentially lethal widespread systemic disease characterized by darkening of the skin as well as the pentad of fever, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and hypergammaglobulinemia

-

Viscerotropic leishmaniasis: Nonspecific abdominal tenderness; fever, rigors, fatigue, malaise, nonproductive cough, intermittent diarrhea, headache, arthralgias, myalgias, nausea, adenopathy, transient hepatosplenomegaly

Patients with visceral leishmaniasis appear thin and cachetic with abdominal distention and protuberance due to massive hepatosplenomegaly (secondary to compensatory production of phagocytic blood cells) (see the image below). The liver and spleen are usually soft and easily palpated in acute disease, with splenic extension to well below the costal margin, and the patient may experience intermittent abdominal distress. Jaundice with mildly elevated enzyme levels is rarely seen and is considered a bad prognostic sign.

Marked splenomegaly (enlargement/swelling of the spleen) in a patient in lowland Nepal who has visceral leishmaniasis. (Credit: C. Bern, CDC) Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites home: leishmaniasis. Resources for health professionals: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/.

Marked splenomegaly (enlargement/swelling of the spleen) in a patient in lowland Nepal who has visceral leishmaniasis. (Credit: C. Bern, CDC) Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites home: leishmaniasis. Resources for health professionals: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/.

Epistaxis and petechiae and ecchymosis from severe thrombocytopenia may occur. Anemia is normochromic and normocytic and caused by various factors, including replacement of marrow by the parasites, splenic sequestration, hemorrhage, hemodilution, and hemolysis. Leukopenia is also observed and may contribute to secondary infections. Thrombocytopenia contributes to the hemorrhagic tendency observed in some cases.

Lymphadenopathy is observed in the African and Chinese forms but rarely is observed in the Indian form. Pedal edema is more common in children. Hair changes, such as alopecia and eyelash elongation, may be present. As the disease progresses, characteristic patchy darkening of the face and trunk has been described and may also affect the hands and feet.

Skin lesions that contain parasites and appear as diffuse, warty, nonulcerative lesions may occur in visceral leishmaniasis, especially in Africa. Although uncommon, xerosis may occur. Complications of visceral leishmaniasis include amyloidosis, glomerulonephritis, and cirrhosis.

In patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and visceral leishmaniasis coinfection, other atypical findings include gastrointestinal and respiratory involvement. Patients have presented with gastrointestinal ulcerations, masses, pleural effusions, and odynophagia. Spread outside of the reticuloendothelial system appears more common.

Unusual clinical presentations of visceral leishmaniasis include the following:

-

Pancytopenia without splenomegaly

-

Immune-mediated hemolysis

-

Generalized lymphadenopathy without hepatosplenomegaly

-

Massive hepatic necrosis

-

Chronic liver disease

-

Retinal hemorrhages (reported in immunodeficient patients)

-

Classic Leishmania major lesion from a case in Iraq shows a volcanic appearance with rolled edges.

-

Atypical appearance of Leishmania major lesion with local spread beyond the borders of the primary lesion. Many of the lesions in cases from Iraq show an atypical appearance.

-

Old World localized cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the trunk of a soldier stationed in Kuwait. This lesion was a 3-cm by 4-cm nontender ulceration that developed over the course of 6 months at the site of a sandfly bite. The patient reported seeing several rats around his encampment.

-

Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis located on the right arm of the same soldier stationed in Kuwait. This 2-cm by 3-cm lesion was located at the exposed area where the sleeve ended. Note the satellite lesions.

-

Active cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion with likely secondary infection in a soldier.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis with keloid formation in a black soldier.

-

Taxonomy of some of the medically important protozoans showing the relative relationship of the Kinetoplastida parasites generally, and Leishmania specifically.

-

Leishmania donovani is one of the main Leishmania species that infects humans.

-

Life cycles of the medically important Kinetoplastida illustrating the similarities and differences between the trypanosomes and Leishmania.

-

Distribution map of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

-

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L tropica and related species and L aethiopica. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html

-

Geographical distribution of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L major. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/index1.html.

-

Geographical distribution of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in the New World. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/

-

Geographical distribution of visceral leishmaniasis in the Old and New world. Source: World Health Organization, Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, Innovative and Intensified Disease Management (WHO/NTD/IDM) Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS), Tuberculosis and Malaria (HTM) WHO, October 2010: https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/leishmaniasis_maps/en/.

-

Distribution map of visceral leishmaniasis.

-

Distribution map of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and leishmaniasis coinfection.

-

The predominant mode of leishmaniasis transmission is a sandfly's bite.

-

Sandfly. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Comparison of a sandfly (left) and a mosquito (right). The sandfly's small size affects the efficacy of bed nets when used without permethrin treatment.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis with sporotrichotic spread.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is generally considered to be an innocuous disease; however, in some parts of the world, especially in tribal areas, even cutaneous disease can have a life altering effect on a person's life. Minimal facial disfiguring can condemn young girls to life without the prospect of marriage or acceptance in society.

-

Leishmaniasis in an Ethiopian woman with a 1-year history of asymptomatic pink-erythematous infiltrative plaque with overlying scale and central crust.

-

Healed cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

-

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions. Photo courtesy of Robert Norris, MD, Stanford University Medical Center.

-

Diffuse (disseminated) cutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Jacinto Convit, National Institute of Dermatology in Caracas, Venezuela.

-

Leishmaniasis recidivans. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Post–kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Courtesy of R. E. Kuntz and R. H. Watten, Naval Medical Research Unit, Taipei, Taiwan.

-

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Visceral leishmaniasis. Courtesy of Kenneth F. Wagner, MD.

-

Marked splenomegaly (enlargement/swelling of the spleen) in a patient in lowland Nepal who has visceral leishmaniasis. (Credit: C. Bern, CDC) Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites home: leishmaniasis. Resources for health professionals: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/.

-

Amastigotes in a macrophage at 1000× magnification. Inset shows the cell membrane and points out the nucleus and kinetoplast, which are required to confirm that the inclusion seen in a macrophage is indeed an amastigote.

-

Free amastigotes near a disrupted macrophage. On touch preparations like this (Giemsa stain, original magnification × 1000), the amastigotes are easier to identify than on other preparations. These stains clearly demonstrate the cell membrane, nucleus, and kinetoplast; all 3 are required for definitive diagnosis.

-

Free amastigote in a touch preparation (Giemsa stain, original magnification × 1000).

-

Light-microscopic examination of a stained bone marrow specimen from a patient with visceral leishmaniasis—showing a macrophage (a special type of white blood cell) containing multiple Leishmania amastigotes (the tissue stage of the parasite). Note that each amastigote has a nucleus (red arrow) and a rod-shaped kinetoplast (black arrow). Visualization of the kinetoplast is important for diagnostic purposes, to be confident the patient has leishmaniasis. (Credit: CDC/DPDx) Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites home: leishmaniasis. Resources for health professionals: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/health_professionals/

-

Illustration of one form of the rK39 test for the serologic diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. It is an easy, very sensitive, and specific test for visceral disease. In this case, the dipstick second from the left shows a positive result and all the rest show reaction only at the control line.