<< Introduction || Next Essay >>

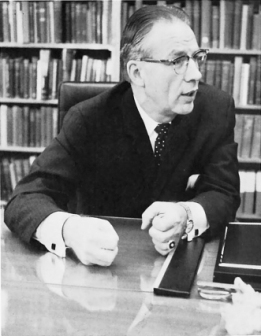

[One should not infer] that students on the Bethel campus did not feel keenly about the issues that have embroiled American youth in controversy. If they had not, they would have been aloof from one of the most important revolutions of modern times and insensitive to the Christian implications of society’s ills. — Carl Lundquist, Bethel president¹

❧

God’s not dead

he moved from Valley Forge to BerkeleyThe system put God in a two by four box of plywood

Amerika Amerika

witch hunts held in Salem

by fighting Joe McCarthydead minds on assembly lines

made mute by standardized truth

in pan clatters

to the kaleidoscope

of mangled bodies

(charred Vietnam babies

two-for-a-penny)frigid bodies in deepening shadows

seeking some warmtha panorama of box car dwellings

done in 3-D cinemascope

swept wide with anguished souls

pumping peanut butter blooddon’t cry baby boy

mummy’ll give you a brand new toy

with plastic eyes and a replaceable heart

just blow in her ear and

she’ll follow you anywhereour people are starving

Where are the friendly balloon men

that soften the chill of autumn? […]Listen to the screaming of my brothers and sisters

skulls cracked up by billyclubs

brains blown apart in Vietnam foxholes

senses numbed with terrorwhile the orchestra plays Vienna waltzes. [..]

Celebrate the ongoing of Life

celebrate the bombed, the bloody carcasses

with their putrefying stench […]we will win

The Revolution will win

The Revolution must win […]

The Revolution is a labor of love

a painstaking mosaic

a pattern of God.— Marjorie Rusche, Class of ‘71²

❧

And suppose we do listen to them? What will we hear? I grant that we will hear some things that are superficial, trivial, hypocritical, rude, and anti-intellectual. I hope this will not tune us out. These are but the peripheral distortions of the real message. — Carl Lundquist³

❧

Of the many facets of the Vietnam experience at Bethel, it was, perhaps unsurprisingly, the periodic anti-war protest events that engendered the most division, ill-feeling, and suspicion between students, faculty, administration, and Conference. Between 1968 and 1972, the campus saw five Moratoria, as many teach-ins, four petitions (both pro- and anti-war), three protests of military recruiters, protests of political speakers, and the publication of an (unfortunately lost to history) underground newspaper.

Students at Bethel were, like those on other campuses, drawn to the war in Vietnam, and they used it as an arena in which to test whether religious-philosophical approaches both old and new were suited to meet the moral and social challenges of modern life. Anti-war protest then was the site of a clash between several different impulses. While a few students and some professors struggled to maintain a pious late 1950s Baptist General Conference sensibility throughout the decade, by 1965-66 that project was obviously untenable on campus. By the time Douglas Olson wrote a letter to the editor in 1966, wincing at the lack of “the Christian viewpoint” in recent Clarion editions and offering a simplistic homily in response (“In answer to some of these controversial items mentioned in the first paragraph, I would like to express what the Bible has to say concerning these things. If you will take out your Bible and turn to the 13th chapter of Romans and read it through, I think you will find some definite answers to what God’s Word has to say concerning these things…”) his time to inject such sentiment into the Vietnam debate was largely over; such contributions looked to readers, then as much as now, like anachronisms harkening back to the Martin Erickson editorials of the late 1950s Standards.⁴

Other students fought — sometimes each other, sometimes staff and administration, and nearly always their sponsoring Conference — to create a new evangelical political culture; but they struggled to articulate a cohesive, authentically Christian response to the pressing social questions of the day — race, war, technology, and increasingly, pollution and the environment. They suffered no shortage of inspiration. The language of the secular New Left permeated life at Bethel just as it did colleges across the nation through institutions such as the National Student Association, Students for a Democratic Society, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And perhaps uniquely for Christians, the inchoate Evangelical Left offered an even more tantalizing approach, blending New Left critiques of American society with evangelical solutions.⁵ One professor at the time recalled that Jim Wallis’ Post-American, an early magazine from the Sojourners organization, was “everywhere” on campus.⁶ Indeed, the language of the evangelical left pervaded the declarations of Bethel’s anti-war protesters; even president Lundquist demonstrated a firm grasp of the language.

Still others abandoned the notion that violence and struggle were valid Christian responses the social and political problems. Drawing on both historic Peace Church theology and an invented tradition of Baptist General Conference inter-war pacifism, these students opted to reject the inherent violence of the Draft system and pursued Conscientious Objector status, arguing that the way of Jesus demanded peace, not conflict.

These three systems of thought — the old BGC mindset, the political Left comprised of the secular New Left and the experimental Evangelical Leftism of the Post-Americans, and pacifism — and many others emblematic of the Vietnam decade clashed as students protested, and in far fewer numbers supported, the war in Vietnam between 1966 and 1972. In that respect, “the Sixties” came late to Bethel; a historian of Calvin College, a fellow Christian institution affiliated with the Christian Reformed Church, recalled that “the new temper” was readily apparent by 1962; “by 1966 it was noisily inescapable; and in 1968-69 it probably reached a climax which relaxed but slightly until 1972.”⁷ If the anti-Vietnam protests came to Bethel somewhat late, they made up for that fact with intensity — five large events dominated the period October 1968 through May 1970, making the anti-war protests the most visible expression of the tumult of the war years on campus.

But those heady days were still years in the future in December 1965. That month, Clarion editor Bill Swenson sounded the first notes of alarm about the war. Drawing on his experiences in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia that summer (it’s unclear whether Swenson was in the military or there in another capacity), Swenson noted that America stood to lose more prestige by continuing an increasingly unpopular war than by agreeing to negotiate in Geneva. The latter course of action might instigate a decline in American standing throughout the world, but it would be a brief one.⁸ Swenson was one of only a handful of writers during this period that took up the task of educating the student body about the pitfalls of the war. They acted against a backdrop of fairly widespread student acceptance of the Johnson administration’s position on the war — an approach entirely consistent with larger Conference thinking.

Far more representative of the kinds of Vietnam-related discussion on campus in the first three-quarters of 1966 was an event held after the Christmas break in early January and a trio of articles which ran in the Clarion through the end of the school year and into the fall of 1966. The January 23rd event, two showings of World Vision’s new eighty minute film “Viet Nam Profile,” was held in Bethel’s fieldhouse. The film showcased “God working despite the war” in a documentary following Warren Harding Withrow, an Army Major-turned-chaplain. Withrow’s comment to the Clarion — that “the military, because of the clash of warfare, is in a position to realize some values in life which the civilians do not, and therefore able to be an aggressive outreach of the church” — linked the American military presence in Vietnam to the potential for more effective Christian missions in that country, a position held by many in the Conference throughout the war.⁹ While the World Vision film appeared fairly agnostic about the larger question of whether or not the United States should be in Vietnam, three Bethel students were far more confident. Writing in March 1965, May 1966, and September 1966, David Hartzfeld, Douglas Ring, and John Sailhamer all argued in various ways that America’s role as a bulwark against rising communism in southeast Asia was justified. Hartzfeld echoed World Vision’s stance, albeit in more forceful terms, writing that “the Church is supracultural and its message alone can reform mankind. Thus I am in favor of resistance against atheism in its military guise in order to give the Church a freer hand in its mission.”¹⁰ Ring and Sailhamer, on the other hand, focused less on the church and more on presenting a strong military: “America must present a united front against communism… We must join or die” (Ring) and “the United States cannot be content with waiting for peace — it must make peace. And to make peace requires force.”¹¹

Sailhamer’s piece was less notable for its innovative contributions to the Vietnam debate than it was for its distinction as the last avowedly pro-war article the Clarion published. Indeed, with the exception of one plea from a missionary toward the end of the war (that man contrasted the work missionaries had been able to do under the Americans with the reprisals guaranteed under communist rule), outright support for the war disappeared from Bethel’s campus. Students and faculty at various points expressed support for the government as an institution and confidence in their leaders’ choices, but no one past September 1966 supported continued U.S. aggression in Vietnam; the “pro-war” position on campus shifted from one of actual support for the war to confidence that presidents Johnson and Nixon’s plans to end the war “with honor” were the best of a set of bad options.

The appearance of a column on October 27, 1966 signaled the finality of that shift, as well as the growing strength of anti-war sentiment among some members of Bethel’s community. The article opened with an attack on the war as brutal as it alleged U.S. action were: “There is one matter that casts its ugly shadow over our lives, over everything we do. This is the criminal, brutal U.S. imperialist aggression against the people of Vietnam. This is the most vicious, savage, uncivilized assault on a small nation in all the annals of human history.” The actions of Johnson, McNamara, Rusk, and Goldberg were the height of hypocrisy, the author claimed, on one hand speaking of the war on poverty, urban renewal, new housing, and hot school lunches, while on the other “operating hundreds of flying crematoria, delivering the devouring seas of flame that engulf villages, towns and the countryside.” In response, the author insisted that

the mind of every American must absorb these facts. The conscience of our people must be aroused by them. We cannot rest until the last piece of U.S. military equipment, the last warship, the last plane, the last unit of military personnel has been removed from the soil of Vietnam. We cannot rest until the people of Vietnam have the full right to determine their own affairs. United, aroused, determined, we can put an end to this crime, this mass murder. We cannot rest until we do.¹²

The next four semesters yielded a variety of Clarion articles on Vietnam. Although it is more difficult to trace connections between these individual articles in a clear timeline, taken as a whole, the period presents a clear progression: students editorialized along two lines, both designed to pave the road toward actualizing protest events on campus. In the first place, students developed an intentionally historical analysis of the Vietnam conflict, aimed toward undercutting the often-simplistic explanations offered by the Johnson administration. Earlier pieces had hinted at this development. Bill Swenson’s editorial, for example, traced the American quagmire back to the earlier Indochinese wars, fought between France and its rebelling colonial holding during the post-war surge in national independence movements. But the most important example of a student historicizing the Vietnam War was a two part series (a planned third part never materialized) penned by Jonathan P. Larson, a history major from Assam, India. (Larson was white, and given his Swedish surname, it is almost certain that his parents were missionaries in the BGC-sponsored Assam mission, active since 1946.) Larson’s lengthy articles set the present Vietnamese war in historical context beginning with the Chinese suzerainty in the 1st century B.C.E. For over two centuries, Larson argued, the Vietnamese had warred with successive invaders, overlords, and imperialists. In the eighteenth century, the English, French, Portuguese, and Dutch vied for trading rights; facing sustained resistance and better opportunities in China, these countries largely abandoned Vietnam to Christian missionaries. A century later, partly in response to the persecution of French Jesuit missionaries and (largely) to balance against increasing British dominance in China, the French increased their military presence, hoping to keep open a Chinese back door. After a further century of French oppression and spurred by the global post-war decolonization movement, the Vietnamese seized their chance to throw off the western yoke. America then, Larson concluded, was placing itself in a long line of foreign imperialists and oppressors.¹³

Larson continued his analysis the next week, describing in detail the effect of World War II on galvanizing popular support for the Viet Minh, the revolutionary leftist coalition headed by Ho Chi Minh. During the war, the Viet Minh gained legitimacy by fighting the Japanese invaders who by 1940 received control of the region from the Nazi-aligned Vichy French government. Much as Mao did in China, Ho led the Viet Minh in guerilla warfare against the Japanese, and when the French managed to reassert control over the country in the wake of the Japanese defeat in 1945, he simply kept fighting. Larson concluded his article by hinting at the U.S. refusal to honor the 1954 Geneva Accords which would have unified the country under Viet Minh leadership, but the promised third and concluding installment never materialized.¹⁴ Larson’s attempts to situate the present American-led war in Vietnam within its historical context demonstrated a new depth of thinking about the war, one which attacked the explanations offered by the American president. Combined with other work focused on defending dissent as a valid public expression, Larson’s work contributed significantly to the intellectual foundations of the upcoming anti-war protest at Bethel.

Secondly, students worked effectively to carve out a place for dissent on campus, legitimizing protest through an intellectual defense of the practice on Christian grounds. The first contribution to this line of argument, however, had no connection to Christianity, or to Bethel. A reprinted editorial from the University of Oregon Daily Emerald told Bethel students why their peers around the country were protesting. College students in the mid 1960s, the editorial surmised, had “little or no contact with developments which led to the present situation in Vietnam.” Their only connection to warfare was negative — in the form of maimed, psychically-scarred, or killed fathers and older brothers who had served in World War II or Korea. Theirs was not the generation that stood idly by as president Eisenhower committed American troops to Southeast Asia in 1956, or as Kennedy escalated American involvement further. Thus, the article concluded, “if [today’s college student’s] body is to be committed to war of another generation’s making, then today’s student wants some answers, and his right to demand them is implicit. This, America, is why they protest.”¹⁵

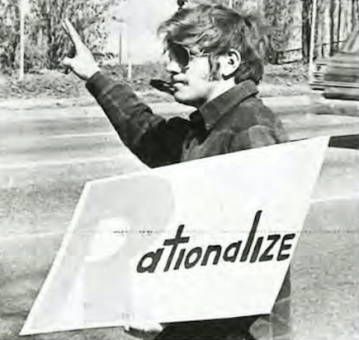

In November 1967, Duane Perkins penned a report on the recent march on the Pentagon in Washington, DC. Perkins noted that although only a tiny minority of the one-hundred thousand person crowd resorted to violence during the march, this was the only aspect of the event most media covered. Accusing president Johnson of cynically promoting the narrative of protesters as violent people, Perkins questioned the ultimate efficacy of continued non-violent protest and warned that unless government were more responsive, protesters might find alternate means of expressing themselves.¹⁶ Although Bethel was hardly to the point of substituting violent for non-violent protest, Perkins’ article did presage the first documented incident of protest on campus. A few months later, a number of students turned out to protest Army recruiters who had ensconced themselves in the Coffee Shop. The Clarion reported that the protesters held a variety of views, ranging from non-cooperation with the government and conscientious objection to opposition to war on moral and religious grounds. They were opposed by another group of students representing what the Clarion deemed the “so what” position. Over the course of the protest, the two groups of students engaged in a “mature, academic manner, exchanging opinions and discussing the problems of the current administration’s Viet Nam policy.” By the end of the day, the “nos” won: they left with four new converts while the Army retreated empty-handed.¹⁷

A week later, chief editor Lynn Bergfalk delivered a ringing endorsement of the right to dissent: “dissent must be one of the most highly revered rights in a free society. The narrow vision and impaired perception which stem from its absence threaten the very values that underlie educational goals and, more generally, the structure of American society and government as a whole.” Prompted largely by the recent issuance of the so-called “Hershey letter” which announced that local draft boards should use the threat of conscription to stymie protest, Bergfalk may have also been speaking in part to Bethel administrators; while no evidence exists to substantiate any repercussions from the previous week’s Coffee Shop protest, it’s plausible that at least some students were cautioned. Bergfalk attacked the critics who always seemed to critique the left-wing and ignore the right, suggesting that their focus was not on “philosophical grounds,” where it belonged, but on externals:

picketing and long hair draw disapproval, while the humanitarian perspective of those criticized is disregarded. There ARE wrongs and injustices existing throughout society, but even ‘Christian’ citizens are apparently too callused to try correcting them.¹⁸

Only when a society had achieved a state of perfection “where protest can no longer serve an important function” would dissent cease to play an important role. Until then, its place in a free and civil society must be defended.

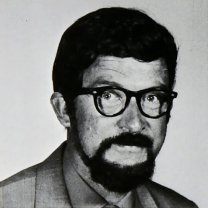

As the new academic year dawned in 1968, the Faculty Senate minutes revealed an academic staff determined to keep abreast of these developments. Webster Muck delivered a report on several areas of student unrest including the Peace Club, the underground newspaper entitled Leaven, and weekly clandestine off-campus meetings.¹⁹ Their concern was well founded; not two weeks later Bergfalk was back, editorializing further on the role of dissent. This time, Bergfalk directed his withering analysis mainly at the far left, arguing that in their tendency to castigate the “unenlightened” they displayed all the boorishness they so disdained in others.

These people, Bergfalk continued, elevated a complicated political discourse to the level of a fetish and reveled in excluding the non-initiated from their discussions. In doing so, they never made a serious effort “to communicate their message in terms comprehensible to those outside of their own pale of alienation.” Bergfalk argued that “one needs to distinguish these dissenters, who call themselves ‘liberals’ or ‘radicals’ from those who dissent constructively. … The former are not liberals or radicals, but merely another type of reactionary.” Lost in the fight between those who “detect a communist conspiracy behind all threatening noises” and those who “voraciously [attack] the establishment” was the notion that citizens “think abstractly and […] deal with complex problems on something more than a simplistic level.” Bergfalk concluded:

A call for sanity might begin with Bethel’s campus.²⁰

It would be nearly a year before Bethel students in any appreciable numbers began to heed Bergfalk’s call.

❧

When protest events began appearing on Bethel’s campus, they were small, unfocused, and generally disconnected with any broader student sentiment. The previously discussed anti-recruiter protest in February 1968 was fairly small — no more than thirty students appeared — and half of the attendance was due to football captain Paul Erickson bringing out “the boys” (presumably members of the football team) to endorse a “so what” position; accordingly, the Clarion noted they “sought to propagate their ideals through the sale of war comics.”²¹ That irreverence seemed to stand through the end of the 1968-69 school year, even in the face of occasional outbursts welling up from the still tiny group of dogmatic anti-war students. Indeed, the 1968-69 academic year saw only one actual Vietnam-related protest. However, this protest, the editorializing of the Clarion, and a protest unrelated to the Vietnam war later in the year, helped to break down the notion Bethel students held that Christian college students could not themselves demonstrate without harming their witness to the world. Thus, 1968-69 saw the notion of protest gain a relatively stable footing, and once achieved, escalated rapidly in intensity and proportion into 1969-70.

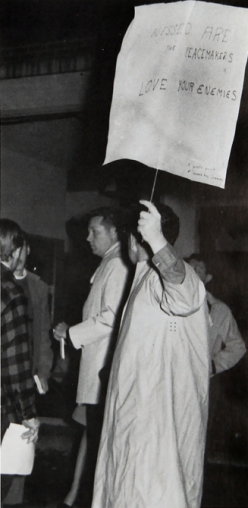

But in 1968-69, the process was still halting, starkly demonstrated on October 19, 1969. Speaking that night as part of the final day of Homecoming 1968 was Walter Judd, a former U.S. Congressman from Minnesota. Opposing him was the stalwart Bethel anti-war institution, Leonard Ray Sammons, class of 1969. Sammons held a lonely picket outside the Fieldhouse while Judd spoke inside on a range of topics from education, theology, Czechoslovakia, Vietnam, race, poverty, and American politics. Sammons’ opposition to the former Congressman stemmed from Judd’s support of the Vietnam War. While other members of the Bethel Peace club had distributed a mimeographed sheet outlining their position, only Sammons actually picketed the speaker.²² Before long, he was assaulted by over a dozen students from the Edgren dorm. As an incredulous Steve Marquardt wrote in the Clarion, these men attempted to physically remove Sammons from his post, accusing him of “acting unChristian,” of smearing Bethel’s reputation as a Christian college, and of “making an ass of himself.” One man shouted from the scrum, “How do you think that looks in front of a Christian college?”²³ Marquardt issued a scathing denunciation of the attempt to silence free speech:

I cannot believe that any man — administrator or student — is righteous enough to dictate to any other the rules by which God judges a person’s spirituality or lack of it. Protecting the image of Bethel will not do for a reason to suppress an individual’s right to express an opinion peacefully, no matter what the opinion is or who the person is, and whether or not he is “making an ass of himself” is entirely irrelevant.

English professor Jon Fagerson responded to the event as well, penning a prayer in the Clarion. “Dear God,” Fagerson wrote,

It’s about Viet Nam. Professors of international law have said the war is illegal. Politicians have said it is suicide. Clergy of all faiths, in great numbers, have said it is immoral. Yet we go on killing […]. When a group of Bethel students gathered to protest this war, another group of Bethel students gathered to mock the protesters.

Fagerson used his prayer as an opportunity to attach apathy. Those who protested the protesters were, at least, taking action. “What about my inaction?” Fagerson wondered, “I have not bothered to find out what is going on over there. I have been too busy. Because the situation is complex and controversial, I have found it safer to make no decision.”²⁴

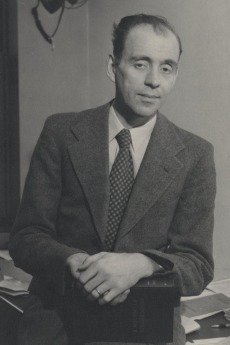

Ten days later Mulford Q. Sibley, a professor at the University of Minnesota and noted pacifist, took up similar themes in a lecture delivered in chapel at the request of the Departments of History and Political Science. Sibley’s lecture, entitled “Justifiable Dissent: The Courage of the Christian Conscience,” continued a line of argumentation advanced in the Clarion over the previous year by arguing that occasionally the religious person must stand in opposition to the predominant currents of the time and become a dissenter. Drawing on the early history of Christianity, Sibley suggested various ways in which Jesus and his early followers exemplified dissent in practice, standing against Pharisees, Herod the Great, the Romans, and the Roman army (early Christians, as told to us by the Roman publicist Celcus, refused to serve in the Roman legions). Sibley argued as well that early Christians had rejected materialism, and that as Christians began to accommodate themselves to — and Christianize — the empire around 200 CE, their dissenting witness was compromised. Christians today, Sibley concluded, should reappropriate the early dissent of the Christians and stand against materialism, war, and the crass values of modern American society.²⁵

His message may have been well received at Bethel (no clues remain in the historical record), but to the Baptist General Conference, Sibley was anathema. In particular, one of his remarks in 1963 on the importance of dissent in civil society had been seized upon as the locus of several controversies in the Conference. In suggesting that American culture was far too monolithic, Sibley had said:

Personally, I should like to see on the campus [of the University of Minnesota] one or two Communist professors, a student Communist Club, a chapter of the American Association for the Advancement of Atheism, a Society of the promotion of Free Love, a League for Overthrow of Government by Jeffersonian Violence (LOGJV), an Anti-Automation League, and perhaps a Nudist Club.²⁶

In 1964, this remark made Sibley the target of a petition started by V.L. Peterson of the Midwest Hebrew Mission to oust the professor and reaffirm moral values.²⁷ And in 1969, Sibley’s remark formed part of the longer diatribe issued by Conference pastor John Ballantine, attacking Bethel for harboring communist influences. Sibley’s presence on Bethel’s campus elicited no discernible response from faculty or students, suggesting that once again, Bethel was far more willing than its sponsoring Conference to entertain so-called liberal ideas.]

At Founders’ Week in February 1968, students “with different perspectives, but united by opposition to the Viet Nam situation” manned a Peace Literature table, the Clarion noted. Presumably the students responsible had publicized their intent beforehand. At least, that was the requested protocol instituted by Bethel’s Student Senate that month, who had, among other things, passed a resolution critical of the Hershey letter of the previous year.²⁸

The most significant protest event of 1968-69 though, had nothing to do with Vietnam — or Bethel — and everything to do with civil rights (another subject over which Bethel and the Conference had historically experienced tension). In the spring of 1968, the Afro-American Action Committee (AAAC) at the University of Minnesota presented a list of demands to administrators including scholarships for black students and the establishment of African Studies classes. By January 1969, with no University action having been taken, the AAAC staged a sit-in of Morrill Hall, the location of the Office of Bursar, Administration, and Student Records. By the next day, University officials capitulated and the sit in ended and a University-established commission reviewed the incident with no further action. Months later, however, the Hennepin County Grand Jury returned indictments against five students for damages to Morrill Hall, estimated at six thousand dollars.

University of Minnesota students were outraged at the indictments which, in their opinion, represented meddling by the government in an internally-resolved university affair. That outrage was shared by Clarion editor Chuck Mybro, who in an editorial on March 27th, reported on a protest planned for April 3rd. Encouraging Bethel students to attend, Mybro added that “it is a worthy cause, and an important one, especially, perhaps, for us at a college like Bethel which has always been against state interference in the educational process.”²⁹

Mybro’s call was supported in the same issue by the candidate for Bethel’s student senate. Gregory Taylor, Bruce Otto, Thomas Mesaros, David Shupe, Richard Berggren, and Maurice Zaffke wrote in a signed statement that “we believe the action of the Grand Jury and the County Attorney is destructive toward resolution of the University’s internal problems. […] The action is politically suspect too considering the source of the complaint which led to the Grand Jury action, the specific naming of the leadership of the [AAAC], and the John Doe nature of the warrant which leaves others subject to arrest.”³⁰

While the Clarion never reported on whether any Bethel students actually did participate in the march, its presence in the newspaper and the endorsement from prominent campus figures suggests a far higher level of comfort with this protest compared to L. Ray Sammons’ protest the October before. So while 1968-69 saw only a few disturbances, those incidences built towards a greater acceptance of protest as a legitimate means of dissent. Events like the Morrill Hall march allowed Bethel students to participate in protests on subjects with which they could readily agree. In doing so, they became accustomed to the symbols and rituals of protest, and by the 1969-70 school year, were ready to engage the most contentious issue of the era: the Vietnam War.

❧

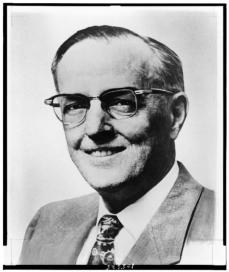

In his June 1969 Annual Report to the Board of Trustees and the Baptist General Conference, president Carl Lundquist devoted nearly five pages to address what he called “The Youth Revolt in America.” In a thoughtful reflection, Lundquist linked the unrest to an increasingly dehumanized world beset by technological innovation that had outstripped moral development. Well aware of the global dimensions of the youth revolt, Lundquist followed the writer John Galbraith in characterizing the malcontents and protesters as merely the tip of the iceberg of student discontent. Only two to three percent of students were radicals, Lundquist quoted from a Fortune article, and an additional seven or eight percent were sympathetic in that they also marched and picketed. More critically, another thirty percent were nonparticipants, yet “felt just as keenly about the burning issues of our times” as the first two groups.³¹ The Fortune article, Lundquist suggested, was a good start, but what was needed was a more precise typology of youth. “To me,” Lundquist said, “the most significant [fronts] appear to be” the Withdrawal Front, the Destruction Front, the Demonstration Front, and the Reformation Front. The first group had “withdrawn to the psychedelic drug pads of the hippies or to the caves of Crete” while the second had lost hope in society entirely and, having turned toward a nihilistic philosophy, sought to destroy the Establishment. The third group was set on sensitizing the American population through demonstration, Lundquist asserted, while the fourth — “and I think by far the largest” — was concerned with reforming society’s institutions from within:

They are the young people who work through the existing channels of democratic action. They write letters, sign petitions, conduct studies, get elected to office, and seek to influence those who are in positions to act. It seems to me that they constitute the true students for a democratic society.

While Lundquist encouraged the older generation to listen to the concerns of youth, discriminate carefully between the four Fronts he had described, and not dismiss outright their concerns, he was not hopeful for such an outcome: “Of course we must ferret out sedition wherever it is fostered by alien ideologies. […] But in the midst of all of this we also must maintain a long view of history. A historical perspective will remind us that since the days of the Indian uprisings, America’s progress forwards has been marked by protest movements.”

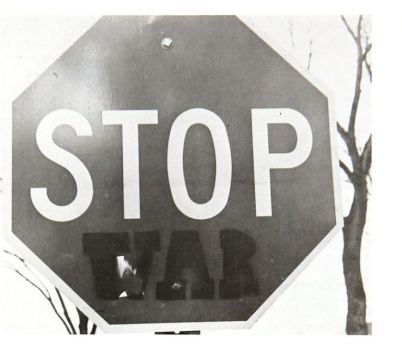

And suppose we do listen to them? What will we hear? I grant that we will hear some things that are superficial, trivial, hypocritical, rude, and anti-intellectual. I hope this will not tune us out. These are but the peripheral distortions of the real message. That message can be heard in the lyrics they sing, the simplistic signs they raise, and the confrontations they force. The notes I hear are the insistence that every human being is a person of importance and worth, that material security ought not have the highest priority in life, that love ought to characterize all of our interpersonal relationship, that right ideals are worth suffering for, that honesty should characterize our actions, that unconventional methods may open exciting new doors into the future, and that whatever ought to be done ought to be done now.

For Lundquist, the youth revolt and Christianity had more in common than most would allow. The ideas students trumpeted — that every person is important, that materialism is not the highest good — were ideas that Christians had espoused for centuries but had sometimes lost sight of; “suddenly they are being sounded dramatically in a variety of strange places. […] This is no time to deplore the new American revolution. This is a time to identify with its valid emphases and to witness about the greatest revolutionist of all — Jesus Christ!”³²

For Lundquist, Christianity and the youth revolt could be two sides of the same coin. Jesus, as the true revolutionary, fulfilled the promise of the youth movement. Indeed, earlier that year, Lundquist had entitled Founders’ Week “Christian Witness in Revolutionary Times” — a conference that included Arthur Blessitt, the well-known Jesus People figure, minister to hippies in Hollywood, and operator of youth center His Place, as speaker.³³ However, as committed to the potential of youth energy as Lundquist may have seemed, particularly in contrast to the kind of thinking within the Conference at the time, it is worth remembering that his administration had also banned the student Peace Literature table at that very same Founders’ Week (in spite of allowing it in 1968; likely, the maturing rhetoric of anti-war protesters that was increasingly disjunct with BGC sensibilities was, by 1969, inappropriate for Conference consumption).³⁴ And in the same piece that contained such eloquent praise of the best aspects of the youth movement, Lundquist had also offered an extraordinarily strict view of the appropriateness of civil disobedience, saying “of course we must deplore civil disobedience, granting those rare instances when in the exercise of conscience, obedience to God takes precedence over obedience to society.”³⁵

Those hedges illustrate the difficulty Lundquist faced as president of a liberal arts college sponsored by a fairly conservative denomination. On the one hand, he was closer to youth and thus more likely to escape falling for the kinds of opprobrium flung by some members of the older generation; on the other, his responsibilities to a sometimes cantankerous Conference forced him to take a harder line against youth than he might have been otherwise inclined to do.

When school began in the fall of 1969, Clarion editor Patricia Faxon proved that splitting the difference merely yields two dissatisfied parties when she wrote an editorial on Lundquist’s report. Lauding him for his “beautiful case for the ‘youth revolt in America,’” Faxon nevertheless took umbrage with his promulgation of eight behavioural principles for students and faculty at Bethel, arguing that punishing social infractions worked directly against the “social revolution” Lundquist had written of:

If the youth revolt is a world wide social revolution, and the violation of social standards is followed by appropriate disciplinary action, it is reasonable to doubt whether the social revolution defended by the president will ever come out of the shadows on evangelical campuses. Social change and legalistic standards constitute incompatible goals.³⁶

Ironically, 1969-70 would see at least parts of the social revolution burst out in full force on Bethel’s campus.

❧

The protests that occurred on Bethel’s campus during the 1969-70 academic year exceeded all earlier years in both intensity and number. Over nine months, students planned and executed three moratoriums and as many teach-ins, circulated flyers, and signed petitions, all centered firmly on the war in Vietnam.

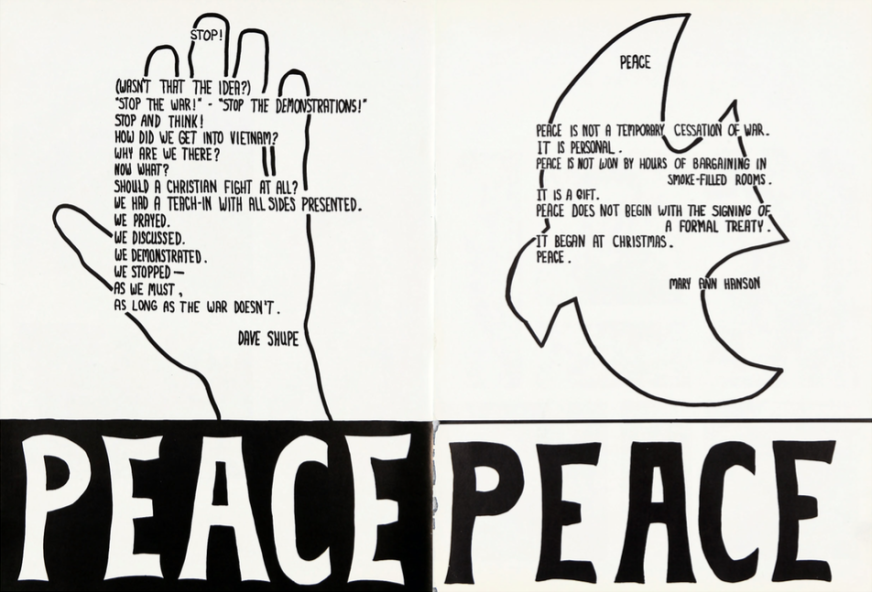

On September 23, 1969, the Student Senate minutes carried the notice that Bethel had been invited through the Inter-Collegiate Coordinating Committee (an organization which allowed twin cities colleges to cooperate with each other on joint ventures — a sort of university-to-university student senate) to participate in the upcoming Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam on Wednesday, October 15. The Moratorium was conceived of as a national day of protest in April of that year by former McCarthy campaign staffers; colleges across the country would stage their own protests concurrent with a large gathering in Washington, D.C. Fifteen twin cities schools planned to participate in an all-day event which mirrored the larger Moratorium. A 9am rally at the University of Minnesota would be followed by a march to the Federal Building, followed by a teach-in and film during which Mulford Sibley would speak. During the evening, students planned a rally, a national speaker, and a torch-lit parade to the capitol. The Bethel minutes reflected some dissatisfaction over how participation would be perceived by the student body; some senators suggested that voting in favor of Bethel’s participation would indicate the Senate took an anti-war stance. Student body president Dave Shupe wondered whether participating Bethel students would be stigmatized.³⁷

While it seems that the Senate never formally endorsed the Moratorium, it was clear from successive pieces in the Clarion that Bethel students were encouraged to attend and participate; Bethel appointed a Moratorium coordinator, student Arne Bergstrom, and arranged for a guest speaker in chapel on the 15th.³⁸ By October 10, Bethel’s plans were nearly in order, Bergstrom reported in the Clarion. A committee of concerned students and faculty met the Saturday before to finalize the events for the day. Under the billing of “The Day of Concern, they included:

- A special chapel service featuring Dr. Philip Hinerman of Park Avenue Methodist Church

- A service of prayer and meditation for peace following chapel

- A teach-in hosted by the Political Science department focusing on the history of Southeast Asia with the lecture titles:

- The Historical Dilemma of Vietnam (Dr. James E. Johnson)

- The War and the American Temper (Dr. William C. Johnson)

- Exploratory Thoughts on War and Peace (Dr. Art Lewis and Dr. Roy C. Dalton)

- American Presence in Vietnam: Two Perspectives (G. William Carlson and Stanley Lemon, missionary to Vietnam)

- A symposium for proponents of differing sides to engage in a formal, moderated discussion

In addition, Bethel students were free to participate in the morning’s rally at the University of Minnesota and the corresponding evening events at the Macalester Fieldhouse featuring Walter Mondale and the torchlit march on the Capitol.³⁹ Further, dean Virgil Olson announced in a memo to faculty that class schedules for the first three periods of the day would be shortened to accommodate the scheduled events. Noting somewhat wryly that “some students will participate in off campus parades and others will, no doubt, join students at the rallies in Minneapolis and the State Capitol,” the dean concluded:

Opinions and feelings will vary regarding the interpretation of the United States’ involvement in Viet Nam. All of us, however, will agree that we want a speedy end to the war, and in this unity let us make Wednesday a day of genuine Christian concern for our nation and the world.⁴⁰

The remarkably pro-protest tenor at Bethel came as something of a phyric victory to Clarion editor Pat Faxon, who remarked in advance of the event that “being against [the war] is now becoming popular. For those who have been involved against it for some time, it’s a little sad. The fact that the stigma of this protest is lessening is a victory, but in the victory, there is a sense of defeat as one recalls the irreparable damage done to some individuals in the change of public opinion.”⁴¹

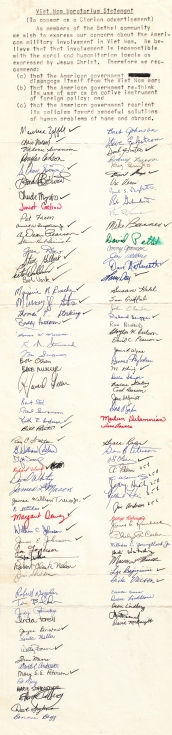

Other than a generic new item covering the October 15 events from a largely city-wide angle (the piece noted among other things the key points of Walter Mondale’s speech), neither the Clarion or the Spire yearbook printed any material reporting on Bethel students’ participation in the day; the Clarion did reprint an excerpt from Mulford Sibley’s October 1968 dissent speech.⁴² Two petitions circulated the week of the Moratorium, however, give significant insight into the level and direction of Bethel’s Vietnam sentiment in October 1969.

The first petition reflected a generic statement from the Concerned Committee of Students and Faculty, the same group that had organized Bethel’s portion of the Moratorium. The statement expressed concern over the war and asserted that the American involvement in Vietnam was incompatible with “the moral and humanitarian ideals as expressed by Jesus Christ.” As a consequence, the petition recommended that the government withdraw, rethink its use of force as “an active instrument of foreign policy,” and that the government pursue peaceful strategies towards problems at home and abroad.⁴³ One hundred and forty-four people signed the petition, including ninety-two students and twenty-two faculty, figures represented over ten percent of the total population of the school (eight percent of the students and twenty-one percent of the faculty).⁴⁴ It’s worth noting that of the seven faculty in the History and Political Science departments, six signed the petition; half of the four English faculty also signed, suggesting yet again that the History, Political Science, and English departments were loci of anti-war faculty.

The petition was not received warmly by others in the college. A note in the October 24, 1969 Clarion reported that a second petition had circulated. Prompted, not as its originators claimed from opposition to the first petition, but as a “purely positive” contribution to the discourse surrounding the Moratorium Day, the petition garnered 130 signatures from students and faculty. Professor Art Lewis and student Rolland Shearer, the article reported, were dissatisfied with the anti-government tones of the Moratorium and felt that the troop drawdowns implemented by the Nixon administration should have been recognized. While the petition’s signatories were never published, disallowing a student-faculty breakdown, the full number represented some 11 percent of the college’s population, almost exactly equal to the anti-war petition. Taken together, the two petitions are suggestive of the contours of pro– and anti-war sentiment on campus. A week later, the second petition itself attracted some controversy when History professor James Johnson wrote a letter in the October 31st Clarion contesting how the pro-government petition characterized the first.⁴⁵

❧

No sooner had the dust settled from the October 15 Moratorium than did planning begin for a November 13 sequel, albeit not at Bethel. The Clarion carried an announcement of the new event, outlining the plans other Twin Cities colleges were making for the day. In addition to a class strike and walkout, students planned a rally on the University of Minnesota mall to hear speeches and rock and roll music. Later in the day, the crowd planned to march to the New Federal Building and surround the structure. Nationally, similar plans were in swing, and as a final ‘event’ for the day, the Minneapolis Moratorium planned to send buses to Washington D.C. for the larger national protest.

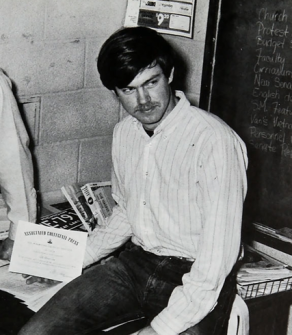

While there are no reports of participation in the Moratorium on Bethel’s campus, five Bethel students hitchhiked to Washington D.C. for the national protest. In a lengthy retrospective published in the Clarion, former editor Marjorie Rusche narrated the group’s experience. After departing Saint Paul, the group found a van of students from the Minneapolis Institute of Arts who were headed to D.C. and traveled with them non-stop to Maryland. Once there, they joined the million-plus crowd waiting to take part in the Moratorium. Surrounded by “Mothers for Peace, Vets for Peace, businessmen, Black Panthers, SDS’ers, hippies, and McCarthyites,” the group waited for hours on the mall for their turn to march along Pennsylvania Avenue. After several hours, a bull-horn announcement told them that there were so many people present that Penn Ave was clogged.

The group left D.C. around 6 pm, hitchhiking with a chemistry professor from Cleveland State and a union worker. From Cleveland to Chicago Rusche and the others rode with a Cook County Welfare Department social worker, discussing “the ever-widening gaps in American society and if it was too late to avert a bloodbath in the streets.” Finally, a former Bethel student dropped them at Bethel. Rusche wrote of her disillusionment the next morning upon waking up to Bethel:

Returning to school Monday was a culture shock. I almost couldn’t grasp that the latest campus “controversy” was whether rock music was sinful or not. I personally was wondering how much longer the country is going to last.

The three days and two nights had cost the students about ten dollars apiece, but for Rusche, “its educational value […] was equivalent to what [she learned] in approximately one semester of college.”⁴⁶

❧

As fall turned to winter turned to spring, Bethel students experienced a period of rest during which they turned to non-partisan activities in which all Bethel students could participate freely. During the week of April 13, students had the option of fasting and donating the resulting money to the General Fund of the Vietnam Moratorium Committee. The Bethel Student Senate had decided it would participate in the fast, but refrained from contributing to the Moratorium Committee; instead, the money would go to the Mennonites for relief work in Vietnam. The plan raised a brief spate of controversy when an effort arose to redirect the funds to the Student Missionary Project, after the bill pledging the money to the Mennonites had passed. Pat Faxon’s editorial on the issues emphasized that while she was not opposed to missions, she was “appalled at the ingrown attitudes” of students. “Bethel students seem to have the general attitude that they and their causes are the only valid group within the sphere of the student world,” Faxon noted. Students at Bethel ought to look up from their parochial doorsteps and realize the vastness of the world of human need; “just because it wasn’t our idea to begin with doesn’t make it bad.”⁴⁷

The donation drive was not the only non-partisan activity students would participate in around the Vietnam War. Earlier, Reuben Omark, a professor at the Seminary, had organized a soap drive to relieve an acute need in the village of Cantho, a few miles south of Saigon. Omark aimed to raise one thousand pounds of soap for his friend, Dr. Quach Bao, a Vietnamese doctor who oversaw healthcare in the village.⁴⁸ And in 1975, a few weeks before the fall of Saigon, the Student Senate voted to send four thousand dollars, plus the result of a collection taken in chapel, to World Vision for its work in South Vietnam.⁴⁹

❧

In May, broader developments shocked Bethel out of the complacency it had developed over the winter and reignited campus protest. On Thursday April 30th, president Nixon announced to the world that U.S. forces had invaded Cambodia, the small and militarily weak western neighbor of Vietnam, in pursuit of thousands of Viet Cong troops hiding in the eastern regions of the country. While the plan might have made military sense — the Viet Cong were indeed camped en masse in Cambodia — its chances of succeeding were questionable at best; the Viet Cong simply melted further westward and avoided contact with U.S forces. Domestically, the plan was a disaster. Nixon dissembled repeatedly, calling it at times an “incursion” or a “non-invasion invasion,” moves his critics viewed with the utmost cynicism. A firestorm of protest erupted across the country. Four students were gunned down by the Ohio National Guard in protests at Kent State, and only eleven days later, two students were killed at Jackson State.

Those killings prompted agonized reflection from Pat Faxon, the editor of the Clarion. In her editorial in the days after the slayings, Faxon used the moment to take evangelicals to task for remaining silent while president Nixon gave them “the run around.” “We are called,” Faxon wrote, “to stand out against what we see as wrong not just in spiritual matters but in all areas of life.”

The campus reaction showed hundred at Bethel were sympathetic with Faxon’s beliefs that evangelical quietism had grown old. While the October Moratorium of the previous fall was carefully planned over its preceding weeks, the May reaction to the Cambodian invasion was swift and ad hoc. Just a few days before the protests, over two hundred students gathered in the basement of Edgren dorm to plan the campus’ response. Within four days, Bethel students had joined with their peers across the Cities, marching on the Capitol with students from the Snelling Avenue area on Tuesday. Bethel students also picketed Snelling Avenue and staged a teach-in on Wednesday. The Clarion reported that the number of participating students had greatly increased over those participating last fall, although it did note that an opposing teach-in was held on Thursday.

The campus reaction showed hundred at Bethel were sympathetic with Faxon’s beliefs that evangelical quietism had grown old. While the October Moratorium of the previous fall was carefully planned over its preceding weeks, the May reaction to the Cambodian invasion was swift and ad hoc. Just a few days before the protests, over two hundred students gathered in the basement of Edgren dorm to plan the campus’ response. Within four days, Bethel students had joined with their peers across the Cities, marching on the Capitol with students from the Snelling Avenue area on Tuesday. Bethel students also picketed Snelling Avenue and staged a teach-in on Wednesday. The Clarion reported that the number of participating students had greatly increased over those participating last fall, although it did note that an opposing teach-in was held on Thursday.

Writing for the Bethel STRIKE committee — the hastily assembled group which planned the events — Maurice Zaffke and Dave Shupe laid out their justifications for demonstrating along Snelling Avenue:

Although we find demonstrations and picket lines usually ineffective, we have decided to hold the Snelling demonstration anyway. Our rationale is to inform the people of St. Paul that at least some Bethelites are opposed to Nixon’s South East Asian policy. We felt a Bethel demonstration would have special significance, especially because of Bethel’s conservative reputation. To state it briefly, if South East Asian policy is in trouble with conservative Bethel youth, it is really in trouble with American youth.

Zaffke and Shupe expressed sympathy with “those charged with public relations for Bethel,” but argued that their actions were part of the Biblical prophetic tradition of standing against injustice. Indeed, as Christians opposed to the war, they faced special trials; the STRIKE statement noted that at a University of Minnesota event on Monday, “the cause of Christ was specifically laughed at” because

Zaffke and Shupe expressed sympathy with “those charged with public relations for Bethel,” but argued that their actions were part of the Biblical prophetic tradition of standing against injustice. Indeed, as Christians opposed to the war, they faced special trials; the STRIKE statement noted that at a University of Minnesota event on Monday, “the cause of Christ was specifically laughed at” because

Jesus was identified with war, reaction, and the American establishment. Because Christians at the rally encouraged people to be saved and not to go on strike. We believe one should be saved and then as a result protest the Asian situation in the same of Christ. We believe that words without works [are] futile, and as a result we are dedicated to oppose the war in Asia in every way we possibly can.⁵⁰

Accordingly, Shupe, Zaffke, and numerous others paced up and down Snelling Avenue bearing placards with anti-war slogans. (Both Zaffke and Shupe would go on to file as Conscientious Objectors.) They were joined by English professor Jon Fagerson, who with two students, enacted a set piece of ‘guerilla theatre’ — a “non-invasion invasion” of Bethel’s campus, complete with brandished machine guns.

On Thursday evening, the Departments of History and Political Science held a teach-in in three parts: responses to the Cambodian invasion, Christian responses to the problem of war, and an open mic session. A programme for the event gave the lecture titles:

- “The Cambodian Incident in a Historical Perspective” (Dr. James E. Johnson)

- “The Cambodian Incident: a Detriment to Sane International Relations” (G. William Carlson)

- “Vietnamization — Cultural Clash” (Dr. Donald Larson)

- “Why a Pacifist Position?” (Maurice Zaffke)

- “The Just War Position” (Dr. William Johnson)

Both Carlson and J. Johnson’s outlines survived, painting a picture of hastily drawn-together presentations that sought to briefly sketch the repercussions of the new aspect of the war. Carlson’s talk emphasized the disastrous effect the new front had on efforts from the international community to end the war, while Johnson hammered home the point that, in contrast to the previous fall when president Johnson was excoriated for escalating the war, the war was now thoroughly Nixon’s.⁵¹

❧

As he had the year before, Lundquist reflected on the previous year’s events in his Annual Report to the Conference. Like the previous year, Lundquist devoted a significant portion of the report to the youth uprising. Unlike 1968-69, Lundquist’s reflection was more strained and less optimistic. While denying that any evangelical school experienced “violence or disruptive action,” Lundquist admitted that “students on the Bethel campus [felt] keenly about the issues that have embroiled American youth in controversy.” Instead of violence, “they simply found ways to express themselves constructively, visibly, and Christianly that made Bethel a stronger institution at the end of the year than at the beginning.”⁵²

Of all the problems facing society, Lundquist identified Vietnam as the central issue. The Cambodian invasion, he suggested, was unfortunate because it simply escalated an already tense situation. It was with great disappointment that Lundquist noted Nixon had been unable “to divulge more fully his reasons for the [the campaign] to make a more convincing case to America’s youth at the time of that action.” The protests, he argued, were linked to the failure of presidential administrations to clearly explain the rationale of the war to students. “No doubt I am more conservative and more patient as an individual than they,” Lundquist admitted, “I have been impressed personally by the fact that three different presidents […] who were much closer to the facts than I am, were sure that this was America’s only course.” Not all were so willing to accommodate authority, Lundquist wrote:

But the generation I serve is not ready to give them that latitude. Officialdom is not sacrosanct, past decisions are not irreversible, endless killing is unwarranted, and a convincing case has not been presented.

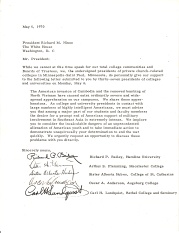

For that reason, Lundquist joined with a number of other college presidents in May to sign a letter protesting the invasion of Cambodia.⁵³

Lundquist’s reflection both continued his earlier injunction to respect youth and listen earnestly to their pleas as well as his hesitancy to endorse any particular aspect of their actions. And in his response to the political grounding of the Vietnam War, Lundquist reflected the position of other prominent evangelicals at the time. Carl Henry, the editor of Christianity Today, expressed the sentiment well when he asked rhetorically, “What special wisdom do clergymen have on the military and international intricacies of the U.S. government’s involvement with Viet Nam? None.” Henry was not alone. Other luminaries and institutions of evangelicalism followed his lead, including Billy Graham and the National Association of Evangelicals.⁵⁴ Yet Lundquist’s signing the anti-war petition suggests a moderation which allowed common sense to rise to the fore. Even as a servant of the Conference, Lundquist was not willing ultimately to suppress his discomfort at certain aspects of the war, even if some of his co-religionists were.

❧

The tension on campus abated significantly during the 1970-71 school year. Only two incidents stand out from the record. In October, English professor Jon Fagerson nearly assaulted a Marine recruiter in the Coffee Shop, so passionate was his disagreement with the practice. Dean Virgil Olson separated the men and calmed the situation. In an apology published in the Clarion, Fagerson expressed disappointment in himself for failing to see the man behind the representative of the system “which thinks that labelling a man as the enemy makes it not responsible for his murder.”⁵⁵ Fagerson’s cynicism about the military was echoed in another letter to the editor a few weeks later which denounced Bethel for allowing the Marines to recruit “future killers” on its campus.⁵⁶

Winter slipped past with little activity; a sense of malaise had settled over the campus as regarded the war. In May, a brief guest editorial appeared in the Clarion announcing the participation of six Bethel students in an April 24th Washington D.C. protest. The six — among them future Conscientious Objector Jack Priggen — had acted to show that Christianity was not merely a set of ideological beliefs by a philosophy which begat action: “We feel that participation in a mass non-violent demonstration is a valid form of protest which is also effective in expressing the thoughts and opinions of those involved.” The tone of the editorial was reflective of a growing sophistication in some sections of the Bethel anti-war movement. Absent the inflamed rhetoric of past years, Priggen and his co-authors’ words sounded serene against the backdrop of previous statements:

“It is significant that the actions of the marchers and speakers at the rally were not only a voice for peace among nations, but perhaps more importantly a concern for peace among men. A concern was expressed for the Black man, the Chicano, workers, the poor, and all others whose basic political freedoms and human rights have been denied. In the Christian ethic we also find and share these concerns as Christ did. Jesus ministered to the physical needs as well as to the spiritual needs of the world. In the Spirit of Christ and of April 24 we extend to you our desire for Peace and our concern for all mankind.⁵⁷

If the 1970-71 year was characterized by a malaise and attendant maturation of anti-war activity, 1971-72 was marked by exhaustion expressed through wan furry. In a lengthy editorial, Paul Swanson narrated the failures leading to the near-total inaction of Bethel’s campus during the planned October 13 Moratorium day. While Swanson and other students in committee had hoped to plan an event similar to other Moratoriums, all of their plans were disrupted. Envisioning the day as a chance to “arouse the Bethel community to a new awareness and intellectual understanding that the war in South East Asia is not over, that pacifism is a misunderstood and often not thought of alternative, and that it is the obligation of Christians not only to pray for peace and the salvation of the world but to do something about it,” the committee sought to have Virgil Olson or Al Glenn speak at chapel. However, neither were available. After three alternates were unavailable, G. William Carlson was asked to speak amidst rumors that a “conspiracy” was afoot to “disrupt” chapel. Then Maurice Lawson, the campus pastor, vetoed Carlson, suggesting that he was “too political” a choice to speak in chapel. After a scuffle over what to do, chapel proceeded as usual with only a brief moment of silent prayer devoted to the Moratorium. Other plans for a teach-in, a literature table at chapel, and a panel discussion fell through in a similar manner.⁵⁸ Instead, Roy Dalton, Chair of History, volunteered to draft a short paper of resources on war, peace, and pacifism. The resulting publication was pushed to the post boxes for students’ reading pleasure.⁵⁹

Similarly, a November 6, 1971 Moratorium was announced, yet no Bethel-specific plans ever manifested. The event was predicted to be the largest yet, drawing over a million people to downtown Minneapolis and bearing the endorsements of the Governor, Minnesota Congressmen, the AFL-CIO, Greater Metropolitan Federation, the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, and the BiPartisan Caucus-Executive Committee.⁶⁰ A dejected editorial from the week before the Moratorium set the mood. Newly-installed Clarion editor and Vietnam veteran Bob Miko’s piece described the irreparable damage inflicted upon Vietnamese society by the presence of U.S. troops and culture: “Then there is what the American presence in Viet-Nam has done. We have completely won them over to the All American God, Money. I saw money become the prime motivator to the Vietnamese. I saw girls who sold themselves for five dollars to support their families on a GI inflated economy. Everywhere there were scars of The American Way of Death as it ripped through a fragile community of people.”⁶¹

The final flurry of activity came at the end of the next semester when news leaked that Nixon had been mining and blockading Vietnamese waters. At Bethel, the news spawned a teach-in, a small protest along Snelling Avenue, a poll, and a petition similar to the one which had circulated in October 1969. Writing after the event, Professor of History G. William Carlson noted that a small group of about fifty students had gathered on the quad to listen to a discussion of the policy and its possible repercussions on American diplomacy with other nations in the region, particularly the Soviet Union.⁶² A poll conducted by the Clarion found that of the student body, forty-nine percent favored the action, thirty-nine percent opposed, and only six percent were indifferent with a forty-three percent response rate.⁶³ One hundred and four students and faculty signed a letter of concern about the policy — ten fewer than had signed the similar 1969 letter of concern — representing twelve percent of the student body and seventeen percent of the faculty.⁶⁴ These activities were the final acts of protest undertaken by Bethel students during the American presence in Vietnam. Perhaps not coincidentally, the end of protest coincided with the move to Bethel’s new suburban campus in Arden Hills.

Years later, G. William Carlson organized a conference at Bethel sponsored by the Consortium of Minnesota Peace Educators and entitled “The Vietnam Experience: Impact, Reflection, and Evaluation.” Bringing together scholars from Bethel, Macalester, the University of Minnesota, Colgate University, and St. Johns University, conference sessions explored how the war was justified, executive power, foreign policy, internal dissent, and lessons from the war. Also presenting was Scott Long, the cartoonist for the Minneapolis Star Tribune during the war.⁶⁵ The next week, the Clarion ran a short piece encouraging students to attend. Not all students had the option; the syllabus for Carlson’s own “Utopian Political Thought” required that students register and attend all sessions.⁶⁶

❧

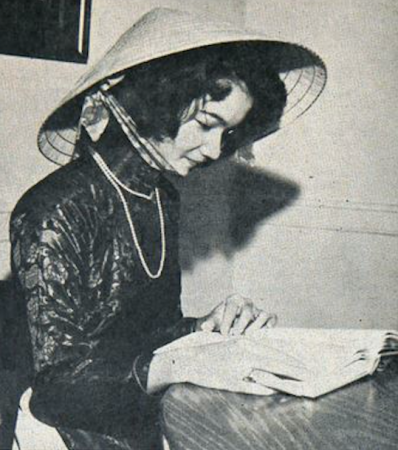

What was it like to experience the war on campus, whether supporter or protester? For those with direct personal experience in Vietnam and the surrounding area, the war was unsurprisingly more complicated and painful than for those who encountered it only through the media. In 1964 a Vietnamese missionary student at Bethel recalled in an interview that “in my country I learned how to be a soldier; four hours every week the government taught me how to shoot a gun.” The constant training and warfare left “no time to think about God,” and the lack of food and water meant that the populace lived in fear; “at night it isn’t safe to leave your house for fear of being killed.”⁶⁷ Tran Van Thuy never reappeared in Bethel publications, but it is probably safe to assume her feelings about the war were more complex than the average rural Minnesotan students; as someone whose goal was to return to Vietnam and found a medical center, Thuy undoubtedly harbored fears of a communist takeover, yet she, unlike most Bethel students, had seen the devastation of the war first hand.

Toward the end of the war, the Clarion published a letter from an unnamed missionary who wrote to the fellow Christian college Westmont with an impassioned defense of the U.S. presence in Vietnam. Had not the Marines evacuated the writer and forty-three fellow missionaries and medical workers from their compound during the Tet Offensive in 1968, they would have perished at the hands of the Viet Cong, the author wrote. Furthermore, the missionaries had witnessed dozens, if not hundred of Vietnamese babies saved by the careful ministrations of military doctors: “It was absolutely unbelievable some of the inventions the young Marine medics came up with to save the lives of the many babies, mostly Vietnamese, who were brought in with lung infections — the rainy season up north takes the little ones off at a sad rate with pneumonia, or combinations of pneumonia with malaria.” “Those of us,” the author wrote, “who have been watching our South Vietnamese friends in their struggle have no doubt at all but what God has used the US. troops to hold off the Communists for a few years and allow His Word to continue its eternal life-giving work to those many who have heard and believed it. We are glad they were sent.” For missionaries like the author, the arguments offered by “all of the malcontents at home” against the war had little meaning, as they were firmly convinced that “the good which has resulted from their having been here — including both temporal and eternal good — far outweighs the bad things.”⁶⁸

Many of those students with military backgrounds felt similarly conflicted about the war — and the actions of anti-war protesters on campus. Ron McNeill had originally been part of the Class of ‘69, but had enlisted after freshman year. McNeill trained as a Hospital Corpsman and served at the Great Lakes Naval Hospital in Illinois for three years before being transferred to the Marines and going in country. He was wounded in the mountainous region of Vietnam, south of Danang and spent seven weeks recuperating before serving the remainder of his four year enlistment at a hospital in Danang. His return to Bethel was facilitated by a personal letter from president Lundquist; McNeill remembered that the “very personal letter and warm invitation [to return to Bethel] sealed my decision, and after discharge, I returned to Bethel.” Back in Minnesota, he found that the war was “extremely unpopular at the time:”

Many students (and professors) were relatively unsympathetic regarding my military experience. There were occasional comments made during classtime that were hurtful, so as a veteran I tended to keep my wartime comments to myself. […] Although I did not disagree with many of the objections to the war, I felt there was some lack of understanding on the part of many. Some students would stand by [Snelling Avenue] with signs and horns, picketing the war effort. In deference to many whom I saw give the ultimate sacrifice to their country, I did not participate.⁶⁹

Bob Goodsell, a member of the football team experienced similar treatment from faculty. During his time at Bethel, Goodsell pursued a commission as an officer in the Marine Corps through the Platoon Leaders Class (an offering similar to ROTC) — an opportunity Goodsell had to pursue at an area school; “[working for a commission] was not considered a popular thing to do at the time and there was no other commissioning source available then like there ar today for Bethel students.” Goodsell had several friends with military backgrounds, and while they were supportive of his military goals, his pursuits “were frowned upon by professors in the history and political science departments.” The professors in the Bible department, on the other hand, were supportive, especially the longtime friend of the Officer’s Christian Fellowship, Bob Smith. When Goodsell graduated, he requested permission to walk in his dress whites, but was refused. In a lonely corner of campus with only a few friends in attendance, Goodsell was sworn into the Marine Corps on the day of his graduation.⁷⁰

As an Air Force brat, Richard Evans’ initial impression of Bethel was one of massive shock. During the winter of his first year, he remembered placing a wet paper towel on his dorm window and watching it freeze solid — a vastly different setting than sunny Guam, where he had lived for two years prior to Bethel. In Guam, his father served as a Colonel at Anderson Air Force Base with the 3rd Air Division. Evans heard, day and night, endless sorties of B-52 bombers departing for Vietnam and believed, along with his friends, that their dads “were fighting to protect the U.S. and its interests.” Things were different at Bethel, Evans recalled:

There was a lot of anti-war sentiment on campus. When I saw “a lot,” you will have to remember that I had just come from an Air Base culture. I don’t remember hearing any anti-war sentiment [in Guam]. So, in reality, maybe the anti-war sentiment was mild or moderate. But from my perspective it seemed pretty strong. I felt like my opinions were definitely right of the majority; I felt like I held minority views.

Evans remembered once accidentally attending a Peace Club meeting (the advertisement led him to believe the club meant something else). “I was in favor of peace. Even my Air Force dad was in favor of peace,” Evans maintained, “But the leader of this group had a hippie look. What he said made me think he was anti-government, anti-war, anti-establishment. I never returned to another meeting.”

Evans’ vivid memories of several important protest events on campus suggest what it was like for those who came from military backgrounds, supported the war, or merely felt that the government knew what it was doing to be on campus during the heady years of 1969-70. Evans spoke at the 1969 Moratorium open mic session, waiting until 11:30pm to tell his story:

I said that my father was an Air Force Officer. I said I had accompanied him to Taiwan and Hong Kong and Japan. I said that [unlike the story a faculty member who had spoken earlier told about racism in the military] I had never heard him speak in a derogatory manner about Asians or others and that most people in the military were not like that. As I finished speaking, I began to cry and had to leave quickly. It was all very emotional for me. I loved my dad.

Evans also recalled an event from which no other record survives. At some point, likely between 1970 and 1972, a number of conservative Bethel students stationed themselves across Snelling Avenue from Bethel and waved a large U.S. flag for several hours, possibly in opposition to one of the Snelling Avenue pickets held by anti-war protesters. “Most of the comments I heard about this were negative, “Evans remembered, “I think some Bethel students were afraid that this would send the message that Bethel was very conservative and they didn’t want that message.” Evans was glad the students did what they did.

Another time, Evans attended a rally on Snelling in front of the State Fair Grounds. The rally featured one of the Chicago 7 — a prominent group arrested after the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago — but Evans’ interests were more salvific than demonstrative; he asked the leader if he could speak to the crowd about Jesus:

Of course, the answer was “No”. I looked out at the crowd, some in skeleton costumes, some seeming angry, some accusing people of being F.B.I. agents, and I was very, very, relieved. The main speaker took out a marijuana joint and smoked it on stage. My Bethel friend and I left soon after.

Like Goodsell, Evans experienced strong anti-war sentiment from some faculty members. He was disturbed by the accounts of racism among servicemen a professor speaking at the 1969 Moratorium relayed. That same professor also posted “anti-war, conscientious objector type messages on bulletin boards.” Although Evans doesn’t remember that faculty member’s name, it is likely that one of the History or Political Science departments was the culprit. Other faculty harbored resentment towards pro-war professors. Dr. Don Rainbow, an assistant dean, reportedly sought to have Bob Smith dismissed from Bethel — the same Bob Smith that Bob Goodsell remembered being so supportive of his career military aspirations.

As for the unnamed anti-war professor, “I never agreed with his point of view,” recalled Evans, “I had read the entire Bible. I knew that God sometimes called people to go to war, even people that didn’t want to do it.” Accordingly, upon turning 18, Evans and some friends went to the Federal Building in Saint Paul and registered for draft cards, in contrast to the single student Evans knew who was a Conscientious Objector. “Interviewers from the government came to interview him. He apparently told them what he believed and why,” Evans recalled. For himself, Evans was “not excited about either joining the military or being shot at, but I decided if I was drafted I would go and do my best to serve the country.”⁷¹

Evans was wrong about the number of Bethel Conscientious Objectors — there were at least thirteen at Bethel, one of whom felt equally alienated from campus culture over the Vietnam experience. Reflecting on his experience in 1976, David Heikkila remembered feeling the same sense of isolation from Bethel’s student population as Evans, Goodsell, and McNeill. When the war finally ended, Heikkila recalled, it was a tasteless victory; the criticism, emotional wounds, and spiritual labels he and other anti-war students had borne from their peers and spiritual leaders on campus left them with “deep sense of alienation.” “In effect, the war and the position it forced us to take separated us from others on campus,” and in spite of campus pastor Maurice Lawson’s “fears that the campus could have been torn apart” by the anti-war students, Heikkila felt that in reality it was the “intolerant patriots” who divided the campus. In his senior testimony in 1973, Heikkila

expressed my feelings about Bethel. I felt that intolerance, or Bethel’s failure to properly handle disagreement during the war resulted in a few of my personal friends deserting the study of Christianity when they could have surrendered to Christ. To them, Bethel’s Christianity was a cop-out It is not with bitterness that I look back on all these feelings about the war and its impact on the lives of Bethel students then, but I feel a profound sense of pain and loss at how we (and I include myself) failed to be the Body of Christ during that time period. I cannot, like Pastor Lawson, blame those who like myself opposed the war, but I must blame the war and its negative effects which we allowed to dominate our lives.⁷²

❧

The estrangement experienced equally by both protesters and supporters points to the deeply alienating nature of Vietnam protest at Bethel. Whether Richard Evans’ discomfort at the openly anti-war statements of his professors and the blame that David Heikkila experienced at the hands of the campus pastoral staff, both sides felt that the other was responsible for a breakdown in communal relations.

In 1969, president Lundquist estimated that between nine and eleven percent of students were firm anti-war protesters while another thirty percent were concerned about the war but relatively apathetic about its resolution. The four war-related surveys taken across the years give some hint of the contours of student opinion. The three student-initiated surveys — the 1969 Moratorium petition, the 1969 pro-government petition, and the 1972 anti-mining letter — all received between 104 and 130 responses or between 10.5 and 13 percent of the school’s population. The Clarion-sponsored poll of Nixon’s mining Vietnamese waters received 452 responses or 43 percent of the student body, a significantly higher response rate. Taken together, the first three surveys suggest a rough breakdown of opinion on campus:

- eight to fifteen percent firmly anti-war

- seventy-three to eighty-four percent apathetic

- eight to twelve percent solidly pro-war

The later Clarion poll substantiates and illuminates that conclusion further by suggesting that the vast middle group — the seventy-three to eighty-four percent — broke substantially in favor of presidential foreign policy, even as they were unwilling to sign a statement from either extreme; forty-nine percent approved of Nixon’s actions, thirty-nine percent disapproved, and only six percent were indifferent. Thus, if the 1972 mining poll can be viewed as a proxy for war sentiment, it seems likely that while the extreme ends of the pro– and anti-war position each attracted fairly equal numbers (about ten percent of the student population) the remainder of campus was somewhat apathetically in support of the war. In other words, the campus broke in favor of the default position: support of the United States government.