Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

ἓulὁgiiΝχlἷx̅ὀἶὄiὀiΝὃu̅ἷΝὅupἷὄὅuὀt

Old and new fragments from Eulogius of Alexandria's oeuvre [CPG 6971 – 6979] *

Of Syrian origin, monk and priest in Antioch, where he presided over the monastery or church

πα α α υ υ α ,1 Melkite Patriarch in Alexandria between 580/581

and 607/608; longtime friend of pope Gregory the Great;2 involved in the dispute over the ecumenical title

of the Patriarch of Constantinople;3 well-known for his defence of the Tomus Leonis 4 and restorer of a

church devoted to Julian the Martyr in Alexandria: 5 the facts we have on the life of Eulogius of

* We would like to thank Prof. Dr. A. Camplani, Dr. J.A. Demetracopoulos and Prof. dr. Peter Van Deun for their valuable

suggestions and corrections in preparing this article.

1 See Photius, Bibliotheca, cod. 226 (244a3-5). Procopius (cf. De aedificiis II, 10, 24) indeed mentions a large church ( ) for

the mother of God, founded by Emperor Justinian in Antioch: α α α ῳπ π α α.

α πα α α π π π ῖ ῳ α · α π ῳ . However, it is

unclear whether this is the same foundation as the one referred to by Photius. – References to Photius' Bibliotheca here and

further down in this article are to the edition by R. Henry, Photius. Bibliothèque, Paris 1959-1991 (Collection Byzantine).

2 Personal letters of Gregory to Eulogius are the following: VI, 61; VII, 37; VIII, 28-29; IX, 176; X, 14; X, 21; XII, 16; XIII, 42-

43. To that should be added the two letters of Gregory addressed to both Eulogius and Anastasius I of Antioch, viz. V, 41 and VII,

31. We refer to the edition by D. Norberg, S. Gregorii Magni Registrum epistularum, Turnhout 1982 (CCSL 140 and 140A). The

letters of Eulogius to Gregory have not survived. See also chapter 7 of the present article.

3 See G.E. Demacopoulos, Gregory the Great and the Sixth-Century Dispute over the Ecumenical Title, «Theological Studies» 70,

2009, pp. 600-621.

4 See Apophthegma 148 of the Pratum Spirituale by John Moschus, where Theodore, the bishop of Dara in Libya, dreams that

Leo says to Eulogius: "I have come to thank you (...), because you have defended so well, and so intelligently, the letter which I

wrote to our brother, Flavian, Patriarch of Constantinople. You have declared my meaning and sealed up the mouth of the

heretics." (transl. by J. Wortley, The Spiritual Meadow (Pratum Spirituale), Kalamazoo, Michigan 1992 [Cistercian Studies Series

139], p. 121). A similar story is recorded in the Synaxarium Constantinopolitanum, February 13. Apart from these legendary

stories, Eulogius is mentioned in act 12 of Constantinopolitanum III (680/681) as the example par excellence of a defender of the

Tomus Leonis (see ACO Ser. II, 2, 2, p. 530, ll. 7-12): ’ α π α α α ,

π π α α ᾳ πα π π α υ πα ,φ υ

α Ἀ α υπ , π αφ π

π φ υ ῳ πα α υπ α α πα υ α .

See also Germanus I of Constantinople's Tractatus de haeresibus et synodis [CPG 8020], PG XCVIII, col. 69B12-C4:

Ἀ ’ π α , α α π α π , ῖ α

π υπ α α, π α α α υ υ α α

π α.

5 Apophthegma 146 of the Pratum Spirituale by John Moschus recounts how after having had a nightly vision of Julian the

Martyr, Patriarch Eulogius had the martyr's church rebuilt: "Then the great Eulogios realised that it was Julian the Martyr he had

1

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

Alexandria are as scant as the writings that survived the more than 1400 years that separate us from him.

In the ninth century Photius' library still held seven mss. exclusively devoted to the Patriarch's writings,

viz. codd. 182, 208, 225, 226, 227, 230 and 280. Notwithstanding some critical remarks about Eulogius'

style of writing and purity of language,6 the large number of pages Photius devoted to Eulogius clearly

prove that he liked what he read. 7 Today, however, we have to content ourselves with some bits and

pieces, little more than snippets of this rich oeuvre. And although it helps that we can still read Gregory

the Great's letters to Eulogius and that in his Bibliotheca Photius went into quite some detail, the fact

remains that the picture we have of Eulogius is not as high-definition, so to speak, as we would have liked.

Hence, Eulogius is, as far as his biography is concerned, almost completely absent from modern

encyclopedias and lexica,8 probably the most comprehensive survey still being that by Joannes Stiltingus

from the year 1868.9 As such, every fine-tuning of the existing material and every discovery of unknown

material is quite welcome.

In this contribution we present a new edition of his so-called Dubitationes orthodoxi, a short text with a

relatively small, but remarkably complex textual tradition; the editio princeps of some lines from

Eulogius' Adversus eos qui putant humanis conceptionibus veram theologiam christianam posse subiici;

the editio princeps of a small fragment preserved in the famous Florilegium Achridense and some remarks

on a number of other writings listed (or not) in CPG 6971 – 6979. As such it is hoped that this article will

serve as a basis for updating the entry on Eulogius in the Clavis Patrum Graecorum and as an incentive

for further study.

seen, urging him to <re>build his church which had been dilapidated for some time and antiquated, threatening to fall down. The

godly Eulogios, the friend of martyrs, set his hand to the task with determination. By rebuilding the martyr's temple from its

foundations and distinguishing it with a variety of decoration, he provided a shrine worthy of a holy martyr." (transl. by Wortley,

The Spiritual Meadow, cit., p. 120).

6 See Photius, Bibliotheca, cod. 182 (127a18-21): Ἔ φ , α , υπ π’ α

, α υ π φ ... Elsewhere Photius refers to, what he calls,

πα υ α υ (cf. cod. 208, 165a13-14)

7 See e.g. also Photius' remark in his discussion of codex 226 (243b10-14): Ἔ υ αφ α α α

, α υ υ α α υ π , α π α α υφ .

8 A list can be found in J.A. Demetracopoulos, Philonic Theology and Stoic Logic as the Background to Eulogius of Alexandria's

and Gregory the Great's Doctrine of "Scientia Christi", in G.I. Gargano (ed.), L'eredità spirituale di Gregorio Magno tra

Occidente e Oriente. Atti del Simposio Internazionale "Gregorio Magno 604-2004" Roma 10-12 marzo 2004, Verona 2005, p.

132 n. 136 and 137.

9 Cf. AASS Septembris IV, Parisiis – Romae 1868, pp. 83-94.

2

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

1 Dubitationes orthodoxi [CPG 6971 and 7697.23b]

The generally albeit misleadingly10 called Dubitationes orthodoxi belong to the genre of the capita, not

however to the rather well-known monastic capita,11 but to the subgenre of the π α or παπ α α,12

short "syllogistische Widerlegungen, welche dem Gegner die begriffliche Inkonsistenz, die

Widersprüchlichkeit, ja die Absurdität seiner dogmatischen Formulierungen nachzuweisen trachten", as

Grillmeier writes, quoting Uthemann.13 Such π α appeared in the early sixth century, quickly became

en vogue and thrived throughout the following centuries. It is a period in which the Byzantine empire saw

a rapid sequence of drastic changes, that inevitably also hightened religious tensions between orthodox

and heretics and between Christians and Jews or Arabs: different groups sought to redefine and strengthen

their position against the outside world. These interconfessional and intraconfessional tensions demanded

a steady production of polemical writings (whether they be homilies, dialogues or, as in this case, aporetic

chapters) with arguments taken from the Scriptures, the Councils, a canon of Fathers and increasingly

from philosophy. Indeed, just like the collections of definitions, which appeared in the same period, such

chapters testify to the increasing conceptual and methodological influence of philosophy on the

discussions concerning faith.14 As Grillmeier writes: "Wir stehen an der Berührungsstelle von Theologie

10 See Demetracopoulos, Philonic Theology, cit., p. 136 n. 152.

11 On the genre of the monastic capita, see the recent tour d'horizon by P. Géhin (Les collections de kephalaia monastiques:

naissance et succès d'un genre entre création originale, plagiat et florilège, in A. Rigo e.al. [ed.], Theologica minora. The Minor

Genres of Byzantine Theological Literature, Turnhout 2013 [Byzantios. Studies in Byzantine History and Civilization 8], pp. 1-

50) and the first chapters of the doctoral dissertation by K. Levrie (L'ordre du désordre: La littérature des chapîtres à Byzance.

Édition critique et traduction du De duabus Christi naturis et des Capita gnostica attribués à Maxime le Confesseur [Doctoral

dissertation], Leuven 2014, pp. 60-75). In September 2014 a round-table was held in Leuven on the genre of the capita ("Chapters

and Titles in Byzantine Literature").

12 Most of the general remarks concerning this subgenre are found in the introductions to the editions of such collections of

π α : K.-H. Uthemann, Antimonophysitische Aporien des Anastasios Sinaites, «Byzantinische Zeitschrift» 74, 1981, pp. 11-26,

especially pp. 16-19; S. Brock, Two Sets of Monothelete Questions to the Maximianists, «Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica» 17,

1986, pp. 121-122 (reprinted in S. Brock, Studies in Syriac Christianity. History, Literature and Theology, London 1992

[Variorum Reprints. Collected Studies Series 357], n. XV). For a more comprehensive, though still summary treatment, see A.

Grillmeier, Jesus der Christus im Glauben der Kirche, Band 2/1, Das Konzil von Chalcedon (451). Rezeption und Widerspruch

(451-518), Freiburg – Basel – Wien 19912 (2004), pp. 94, 96 and 99-100.

13 Cf. Grillmeier, Jesus der Christus, 2/1, cit., p. 96 and K.-H. Uthemann, Syllogistik im Dienst der Orthodoxie. Zwei unedierte

Texte Byzantinischer Kontroverstheologie des 6. Jahrhunderts, «Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik» 30, 1981, p. 107.

Unfortunately, Grillmeier's list of works belonging to this subgenre is far from exhaustive, lacking, for one, several of the writings

by Maximus the Confessor.

14 See e.g. the famous article by C. Moeller, Le chalcédonisme et le néo-chalcédonisme en Orient de 451 à la fin du VIe siècle, in

A. Grillmeier – H. Bacht (edd.), Das Konzil von Chalkedon: Geschichte und Gegenwart, I, Der Glaube von Chalkedon, Würzburg

1951, pp. 637-643.

3

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

und Philosophie oder, konkreter, vor dem Versuch, die christologischen Aussagen nach den Gesetzen der

aristotelischen Logik und Syllogistik zu untersuchen und diese Mittel in der Polemik einzusetzen".15 Soon

after the appearance of the genre a degree of standardization can be noticed both in the arguments and in

their wording.16

The Dubitationes orthodoxi are directed against those who profess only one nature in Christ or, as T.

Hainthaler puts it, "gegen die bloße 'mia physis' mit dem Hinweis, daß man dann ja eine Wesensgleichheit

von Gott (Vater, Logos) und Sarx annehmen müßte".17 Also in this case, most, if not all of the arguments

are of a highly standardized nature: they are found throughout the anti-monophysite literature, and,

mutatis mutandis, in other christological disputes.18 The line of reasoning is concise, stripped down to the

essence with a mostly bipartite ("if A, then why B? and if B, then why not A?"), sometimes tripartite, i.e.

syllogistic, structure ("if A and if B, then how come C?") – in the translation that follows our edition we

have highlighted the structural elements by quoting them between brackets –. In most cases, the argument

starts from a monophysite statement which is then shown to result inevitably in one of three situations,

viz. an "impossibility to answer", an "absurdity" or "orthodoxy".

The agressive and polemical wording suggests these chapters to have been conceived as a direct attack

against the monophysites. They do not convince, they deal blows to the adversaries, corner them

immediately by stressing the inevitability of the conclusion. But was this really the purpose of these

chapters? Similar chapters were also devised by the adversaries, equally tressing the inevitability of their

15 See Grillmeier, Jesus der Christus 2/1, cit., p. 94. Very similar is K.-H. Uthemann, Definitionen und Paradigmen in der

Rezeption des Dogmas von Chalkedon bis in die Zeit Kaiser Justinians, in J. van Oort – J. Roldanus (edd.), Chalkedon:

Geschichte und Aktualität. Studien zur Rezeption der Christologischen Formel von Chalkedon, Leuven 1997 (Studien der

Patristischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft 4), cit., p. 60.

16 Examples are given by P. Bettiolo, Una raccolta di opuscoli calcedonensi (Ms. Sinaï Syr. 10), Louvain 1979 (CSCO 404;

Scriptores Syri 178), pp. 12*-15*. This volume presents an Italian translation of the Syriac texts edited by the same scholar in

Una raccolta di opuscoli calcedonensi (Ms. Sinaï Syr. 10), Louvain 1979 (CSCO 403; Scriptores Syri 177). In the rest of this

article these volumes will be referred to as Una raccolta [transl.] and Una raccolta [ed.] respectively.

17 Cf. T. Hainthaler in A. Grillmeier, Jesus der Christus im Glauben der Kirche, 2/4, Die Kirche von Alexandrien mit Nubien und

Äthiopien nach 451 (unter Mitarbeit von Theresia Hainthaler. Mit einem Nachtrag aktualisiert), Freiburg – Basel – Wien 2004, p.

68.

18 Compare e.g. ʹ of the Dubitationes orthodoxi with the first part of chapter αʹ of Maximus Confessor's Capita xiii de

voluntatibus [CPG 7707.18], a short collection of π α from the monothelite controversy – we quote from the edition in our

doctoral dissertation (Epifanovitch Revisited. (Pseudo-)Maximi Confessoris Opuscula varia: a critical edition with extensive notes

on manuscript tradition and authenticity, Leuven 2001, p. 682) –: α ῳ α α ,

πα α υ, α α α πα α α (see also the old edition by ἥέδέΝ ἓpiἸ̅ὀὁvič,

М і і і .М И ѣ , Kiev 1917, p. 65, ll. 11-12). As such, we do not

pretend that the Apparatus fontium et locorum parallelorum is exhaustive.

4

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

conclusions and it is hard to imagine that anyone would believe that these embryonic arguments could

actually overpower the arguments of the other party. Why would a monophysite go through the trouble of

reading this anyway? The first lines of John of Damascus' Adversus Nestorianos [CPG 8053] suggest

another possibility,19 viz. that such π α were intended as a mnemonic device, embryonic arguments

that could be expanded in altercations, a theological arsenal so to speak. The protasis then words the

possible argument of a monophysite, the apodosis the counterargument that can be brought forward by his

orthodox interlocutor. This can also be seen e.g. in Anastasius I Antiochenus' Adversus eos qui in divinis

dicunt tres essentias [CPG 6958].20 However, this interconfessional use of the π α is only one side of

the picture. The other side is that these and similar texts inevitably also served an intraconfessional

purpose in strengthening the confessional identity of the coreligionists. As worded by Averil Cameron in

discussing Christian – Jewish polemical literature: "they helped to define the limits of the safe Christian

world, beyond which Christians must not go", and further down "Disputation literature, polemics against

outsider groups (...) all had their uses in this strengthening of ideological boundaries to define a

Christian".21

The aforementioned high level of standardization of the wording and the arguments considerably limits

the possibilities of pinpointing such π α to a certain place and date and, thus, of attributing it to a

certain author. In the case of the Dubitationes orthodoxi this porblem is further complicated by the

existence of two, clearly distinct versions.22 The shorter one has seven chapters (henceforth D.O.7): it

exists not only in its Greek original, in which case it is attributed to Eulogius π πα Ἀ α α , but also

in a seventh-century Syriac translation headed by the name Phokas. The longer version is made of twelve

chapters (henceforth D.O.12), i.e. the seven chapters of the shorter version plus five extra at the end,

sometimes has a slightly different wording and adds some extra lines in chapter ʹ. This version is

anonymous and is found in two different families of mss.: one family consists of the five mss. of the

19 See the edition by B. Kotter, Die Schriften des Johannes von Damaskos, IV. Liber de haeresibus. Opera polemica, Berlin –

New York 1981 (PTS 22), p. 263: υ φ α υ· πα ῖ , , α

υ α α πα , φ υ α π ; π · φ υ α ,

. Ἐ α α πα υ · υ α α α

α α απ ; π ·Ἄ π , α ῖ α α...

20 See the edition of this text by K.-H. Uthemann, Des Patriarchen Anastasius I. von Antiochien Jerusalemer Streitgespräch mit

einem Tritheiten (CPG 6958), «Traditio» 37, 1981, pp. 73-108 (see e.g. ll. 475-478 [p. 94]).

21 See A. Cameron, Disputations, Polemical Literature and the Formation of Opinion in the Early Byzantine Period, in G.J.

Reinink – H.L.J. Vanstiphout (edd.), Dispute Poems and Dialogues in the Ancient and Mediaeval Near East. Forms and Types of

Literary Debates in Semitic and Related Literatures, Leuven 1991 (OLA 42), p. 107.

22 The following two paragraphs in the present contribution only present a short overview. The details can be found further down.

5

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

Doctrina Patrum [CPG 7781], while the other family of four mss. has no clear relationship with the

Doctrina Patrum.

The presence or absence of the words and , suggests a similar division. They are used

exclusively in the parts proper to D.O.12, i.e. the middle part of ʹ and ʹ– ʹ, and are typical of the less

combative style of the lines proper to D.O.12. Moreover, it seems noteworthy that in D.O.7 the ao. imp. 2

sing. π is used, while in D.O.12 only the plural πα appears. This coming to the fore of the second

person plural in D.O.12 is also noticeable in chapter ʹ, as can be concluded from a comparison of the

following two passages:

D.O.7 and its Syriac translation D.O.12

φα . α α . ῖ Ν Ν ῖ

Ν Ν ῖ Ν Ν

As concerns the additional lines in chapter ( ʹ), there are some elements which make them look

suspicious and which suggest that they are later additions. Not only do these additional lines break with

the conciseness of the foregoing and following chapters, while omitting them changes nothing to the

meaning of the caput, even if, as Bettiolo puts it: "lo impoverisce recidendo uno sviluppo forse dei più

interessanti sotto il profilo dell'approfondimento filosofico".23 There is also the parallel with chapter 19 of

the Syriac version of Probus' Dubitationes adversus Iacobitas, which in the Italian translation by Bettiolo

runs like this:24

Dio Verbo è connaturale alla carne che fu da lui assunta o è un'altra natura? Se (le) è

connaturale, come la Trinità non divenne una Quaternità? Se invece la carne di Dio Verbo

è un'altra natura, come Cristo non è due nature?

Also in this case, no extra explanation of the first sentence was needed to make the chapter work. And,

finally, the sequence of the sentences – π φυ (ll. 3-4) and α 1 – π α (ll. 5-6), is rather

strange, mainly because of the change of subject of φυ α into a simple .

In short, we are convinced that D.O.7 is the original version and that someone, possibly, but – as will

be shown further down – not necessarily the compiler of the Doctrina Patrum, used it as the nucleus for

D.O.12. Whether the five extra chapters were written for that occasion or were drawn from another source

is unclear. In any case, if indeed D.O.12 is a secondary expansion of D.O.7, it might explain the fact that

no author is mentioned.

But what about the authors mentioned in D.O.7 and its Syriac translation? According to the latter a

certain Phokas would have written the text. But while we found no possible Greek author of that name,

23 Cf. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [transl.], cit., p. 15* n. 23.

24 Cf. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 12, l. 30 – p. 13, l. 3 and [transl.], cit., p. 9, ll. 24-27.

6

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

there is the quite famous Phokas bar Sargis, who translated the Corpus Dionysiacum into Syriac.25 He was

long believed to have lived in the 8th century26 until S. Brock discovered that in his Discourse on the

Myron Jacob of Edessa quotes several times Phokas' translation of the Corpus Dionysiacum. As a

consequence Phokas' translation cannot but antedate Jacob's death in 708.27 The translation of D.O.7 fits in

remarkably well with this date, as the period before the year 708 is certainly "coerente all'interesse ancora

vivo a quella data di alcuni dei testi ivi racchiusi, quelli teologici appunto", as Bettiolo states about the

whole of the collection of texts in which the Syriac translation of D.O.7 is found.28 In other words, Phokas

is more likely to have been the translator than the author of the text.

Remains Eulogius of Alexandria, mentioned as author in the Greek original of D.O.7. As already said,

the standardized language typical of the aporetic subgenre hampers the possibilities of confirming this

attribution. Still, there is nothing that contradicts it either. Eulogius' dealings with the monophysites and

with Cyril of Alexandria's αφ α -formula are well-attested from what Photius writes, as

is his predilection for the aporetic. In other words, there is no reason to reject or question the generally

accepted attribution in the Greek mss.29

One last question needs to be addressed before we turn to the edition of the Dubitationes orthodoxi,

viz. whether there is a connection with Maximus the Confessor.30 The question is relevant because Fr.

Combefis included D.O.7 in his Opera omnia-edition of Maximus the Confessor and P. Sherwood 31

numbered it in such a way, i.e. Op. 23b, that at least the suggestion is made that (together with the two

25 On Phokas' translation of the Corpus Dionysiacum, see most recently M. van Esbroeck, La triple préface syriaque de Phocas,

in Y. de Andia (ed.), Denys l'Aréopagite et sa postérité en orient et en occident. Actes du Colloque International Paris, 21-24

septembre 1994, Paris 1997 (Collection des Études Augustiniennes. Série Antiquité 151), pp. 167-186.

26 Cf. still G. Wiessner, Zur Handschriftenüberlieferung der syrischen Fassung des Corpus Dionysiacum, Göttingen 1972

(Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, I, Philologisch-historische Klasse 3/1972), pp. 168 and 199.

27 Cf. S. Brock, Jacob of Edessa's Discourse on the Myron, «Oriens Christianus» 63, 1979, p. 21. According to Brock there is

reason to narrow the date of Phokas' translation down to the years 684-686.

28 Cf. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], cit., p. 6*.

29 Cf. M. Richard, Iohannis Caesariensis Presbyteri et Grammatici Opera quae supersunt, Turnhout – Leuven 1977 (CCSG 1), p.

XVIII (quoted further down, in footnote 33) and more recently T. Hainthaler in Grillmeier, Jesus der Christus 2/4, cit., p. 67 and

Demetracopoulos, Philonic Theology, cit., p. 136.

30 In the following paragraph we refer with Op. to Maximus' Opuscula theologica et polemica [CPG 7697] and with Add. to the

so-called Additamenta e variis codicibus [CPG 7707]. The number that follows Op. or Add. is the number as used in the CPG

(e.g. Op. 23a refers to CPG 7697.23a). Op. 23a – Add. 22 indicates that Add. 22 is but an alternative, in this case lengthened

version of Op. 23a.

31 Cf. P. Sherwood, An Annotated Date-list of the Works of Maximus the Confessor, Roma 1952 (Studia Anselmiana 30), pp. 30-

31.

7

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

short fragments that follow Op. 23a32 and the selection of definitions referred to as Op. 23c) Op. 23b is

part of an appendix added by Maximus to Op. 23a – Add. 22.33 However, Maximus' authorship of Op. 23a

– Add. 22 is, we believe, anything but certain and most likely to be rejected.34 And the number of mss. that

contain Op. 23b in the wake, so to speak, of Op. 23a – Add. 22 is too small (it is the case only in one of the

six families of mss. that contain Op. 23a – Add. 22, i.e. in only four out of 22 mss.) for this sequence of

the texts to be the result of anything else than coincidence.

But let us turn to the edition of the Dubitationes orthodoxi. The following list presents the extant mss., all

of which were also collated:

I. Traditio 7 capitum (D.O.7)

a. Greek text, attributed to Eulogius of Alexandria

Ac Atheniensis, Bibliothecae Nationalis 225 (s. XIV), ff. 181v-182

Ug Vaticanus graecus 504 (a. 1105), f. 146va-b

Uh Vaticanus graecus 507 (a. 1344), ff. 128v-129

Ui Vaticanus graecus 508 (s. XII-XIII), f. 203r-v

b. Syriac translation, attributed to Phokas

Syr Sinaïticus syriacus 10 (s. VII, post 641), ff. 5-7

II. Traditio 12 capitum (anonymous; D.O.12)

a. Mss. containing the Doctrina Patrum

DPatr(A) Vaticanus graecus 2200 (s. VIII-IX), pp. 233-236

DPatr(B) Athous, Vatopediou 594 (olim 507) (s. XII in.), ff. 98-99

DPatr(C) Oxoniensis, Bibliothecae Bodleianae, Auctarii T.1.6 [Micellaneus 184] (s. XII), ff. 121v-122v

DPatr(D) Parisinus graecus 1144 (s. XV), ff. 120-122v

DPatr(E) Vaticanus graecus 1102 (s. XV), f. 409r-v

b. Mss. with no clear link with the Doctrina Patrum

Cc Atheniensis, Metochiou tou Panagiou Taphou 145 (s. XVI), ff. 494-495

Mb Mediolanensis, Bibliothecae Ambrosianae Q74 sup. [681] (s. X), f. 206r-v

32 Since the edition in 1909 of the third volume of Stählin's Clement-edition, the first fragment, entitled υ

π υ υ Ἀ α α, π α υ, is generally known as fragment 37 of Ps. Clement of

Alexandria's De providentia (ed. O. Stählin, in zweiter Auflage neu herausgegeben von δέΝ ἔὄὸἵhtἷlό, zum Druck besorgt von

Ursula Treu, Clemens Alexandrinus, III. Stromata Buch VII und VIII. Excerpta ex Theodoto – Eclogae propheticae – Quis dives

salvetur – Fragmente, Berlin 19702 [GCS 172], p. 219, ll. 15-22). It consists of three definitions of α, followed by three

definitions of φ . The second fragment following Op. 23a is a definition of π α taken from Maximus' Epistula

13 (see PG XCI, col. 528A14-B7).

33 Richard (Iohannes Caesariensis, cit., p. XVIII) e.g. explicitly states: "Le seul texte original d'Euloge d'Alexandrie qui n'ait pas

été contesté est l'opuscule Ἐπαπ υπ α π α π φ , anonyme dans la Doctrina

Patrum, ch. 24, I, mais dont les sept premières sont citées sous le nom d'Euloge par Maxime le Confesseur."

34 For the reasons we have for rejecting Maximus' authorship, see our doctoral dissertation, Epifanovitch Revisited, cit., pp. 695-

701. We are reworking this part of the dissertation for a future publication. Maximus' authorship has recently been rejected also

by B. Gleede, The Development of the Term υπ α from Origen to John of Damascus, Leiden – Boston 2012 (Supplements

to Vigiliae Christianae 113), pp. 143-144.

8

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

Mo Mosquensis, .И.М., graecus 394 [Vlad. 231] (a. 932), ff. 103v-104v

Ul Vaticanus graecus 1101 (s. XIII-XIV), ff. 308v-309

Before we try to assign these witnesses to their proper place in the stemma, two preliminary remarks

should be made, both relating to the limited length of the text. In the first place, this shortness almost

inevitably results in a paucity of decisive faults and variants. Fortunately, for each of the three families of

mss. this can be remedied – at least partly and with all due carefulness – by taking into account earlier

editions of texts in the immediate surroundings of D.O.7 and D.O.12. In the second place, listing the faults

and variants proper to each single ms. would be of little or no avail: again because of the shortness of the

text the reader can easily find them in the critical apparatus accompanying the text.

1.1 The seven chapters: the Greek tradition and its Syriac translation.

The family Ug Ac Ui Uh is quite famous among the mss. that transmit Maximus the Confessor's

literary oeuvre.35 Suffice it to repeat the stemma and confirm it for the present text:

μ

μ* μ**

Ug x Ui

Ac Uh

Unfortunately, as for most of the other texts that belong to the same series, 36 these mss. are

characterized by only a small number of faults and variants: there are no readings proper to Ug or Ui,

while Ac, Uh and ** stand out by only one fault each.37

As to , the common ancestor of this family, the situation is quite different, or at least seems to be

different. On more than 20 occasions it presents a reading that differs from D.O.12. However, a

comparison with the Syriac translation will reveal that most of these differences at least go back to the

second half of the seventh century.

This Syriac translation is preserved in a melchite estranghelo ms., viz. number 10 of the Syriac mss. in

Saint Catherine's Monastery in the Sinaï. On the basis of a chronicle on ff. 42-53 A. de Halleux identified

35 For a description of these mss. (with bibliography) we refer to our article Precepts for a Tranquil Life. A new edition of the Ad

neophytos de patientia [CPG 7707.32], «Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik» 64, 2014, pp. 247-284.

36 For this series of texts, see the comparative table presented on pp. 254-256 of the article mentioned in the foregoing footnote.

37 For Ac, see (α') 3 φ α for φ α ; for Uh, see ( ') 2 υ πα for υ α πα , which is a

variant reading in for πα α υ; for **, finally, there is the reading φ for φ on ( ') 8, which

coincidentally is also found in Cc.

9

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

the death of emperor Heraclius on May 26th 641 as the terminus post quem for this ms.38 and there is

indeed reason to believe that Syr dates back to the second half of the seventh century.39 D.O.7 is found as

the fifth text (ff. 5-7) of an acephalous collection of Chalcedonian texts (ff. 2-41), which was partly edited

'tel quel' and translated into Italian by P. Bettiolo.40 The collation for the present article was done on the

basis of Bettiolo's edition.

Now if we look at the passages where D.O.7, or better , the common ancestor of that version, differs

from D.O.12, we see that in the majority of the cases Syr confirms the text of – we list the readings for

which differs from D.O.12 and underline the readings which are also found in Syr –:

(αʹ) 1 (om. of 2 [coincidentally also in DPatr(E) and Cc]); ( ʹ) 1 (add. of after ;

α for ῖ α [coincidentally also in DPatr(B)] and addition of after α );

( ʹ) 3 ( α for ῖ α [coincidentally also in DPatr(ABE)] and φ for

φ ); ( ʹ) 4 (transposition of before 41

); ( ʹ) 1 (πα 'α φ for

π φ ); ( ʹ) 2 (om. of υ–π π υ [coincidentally also in Mb Cc]); ( ʹ) 3/7 (om. of

– π ); ( ʹ) 1 (φα .42 α α for ῖ ῖ ); ( ʹ) 2

( α for α α 43 and om. of υ); ( ʹ) 2/3 ( for ῖ

); ( ʹ) 4 (om. of α ' α ); ( ʹ) 5 (om. of ); ( ʹ) 1/2 (om. of – α 1); ( ʹ)

2( υ α πα for πα 2

– υ ); (ϛʹ) 3 ( υ αΐ

2

πα α for

ΐ – ); (ϛʹ) 4 (add. of before 1 44

); (ϛʹ) 5 (the correct reading α 45

while D.O.12 reads , or ); ( ʹ) 1 ( while D.O.12 reads ); ( ʹ) 2

(om. of 46

); ( ʹ) 2/3 (om. of 3 – α ).

For the readings we underlined, the evidence of Syr shows that they go back at least to the seventh

century. For smaller problems, like those with the verb ῖ α (cf. [ ʹ] 1 and [ ʹ] 3) and that with the

position of (cf. [ ʹ] 3) and (cf. [ ʹ] 4), it is unclear whether the translation is made carefully enough

to show this. In other words, only the readings on ( ʹ) 4, ( ʹ) 1/2, ( ʹ) 2, (ϛʹ) 3 and ( ʹ) 2/3 can be

considered with a sufficient degree of certainty as faults which were made during the transmission of the

Greek text of D.O.747.

38 Cf. A. de Halleux, À la source d'une biographie expurgée de Philoxène de Mabbog, «Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica» 6-7,

1975-1976, p. 254.

39 Cf. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], cit., p. 6* (and the bibliography mentioned there).

40 See Bettiolo, Una raccolta, cit. For Op. 23b, see pp. 6-7 [ed.] and pp. 4-5 [transl.] respectively.

41 There is no trace of in Syr.

42 Instead of φα Syr reads something like φα πα .

43 Syr seems to read something like α .

44 While Ug Ac Ui read , Syr reads, if we translate it into Greek, .

45 Syr reads something like – and is closer to D.O.7 than to D.O.12. The simple addition of a preposition ܒbefore Νܚܕ

ΧܡܕܡΨ would make the reading of Syr identical to that of D.O.7.

46 In Syr is positioned after α ([ ʹ] 2).

47 Whether these faults were made by or by one of its ancestors is impossible to establish and irrelevant for the present purpose.

10

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

1.2 The twelve chapters

1.2.1 The Doctrina Patrum

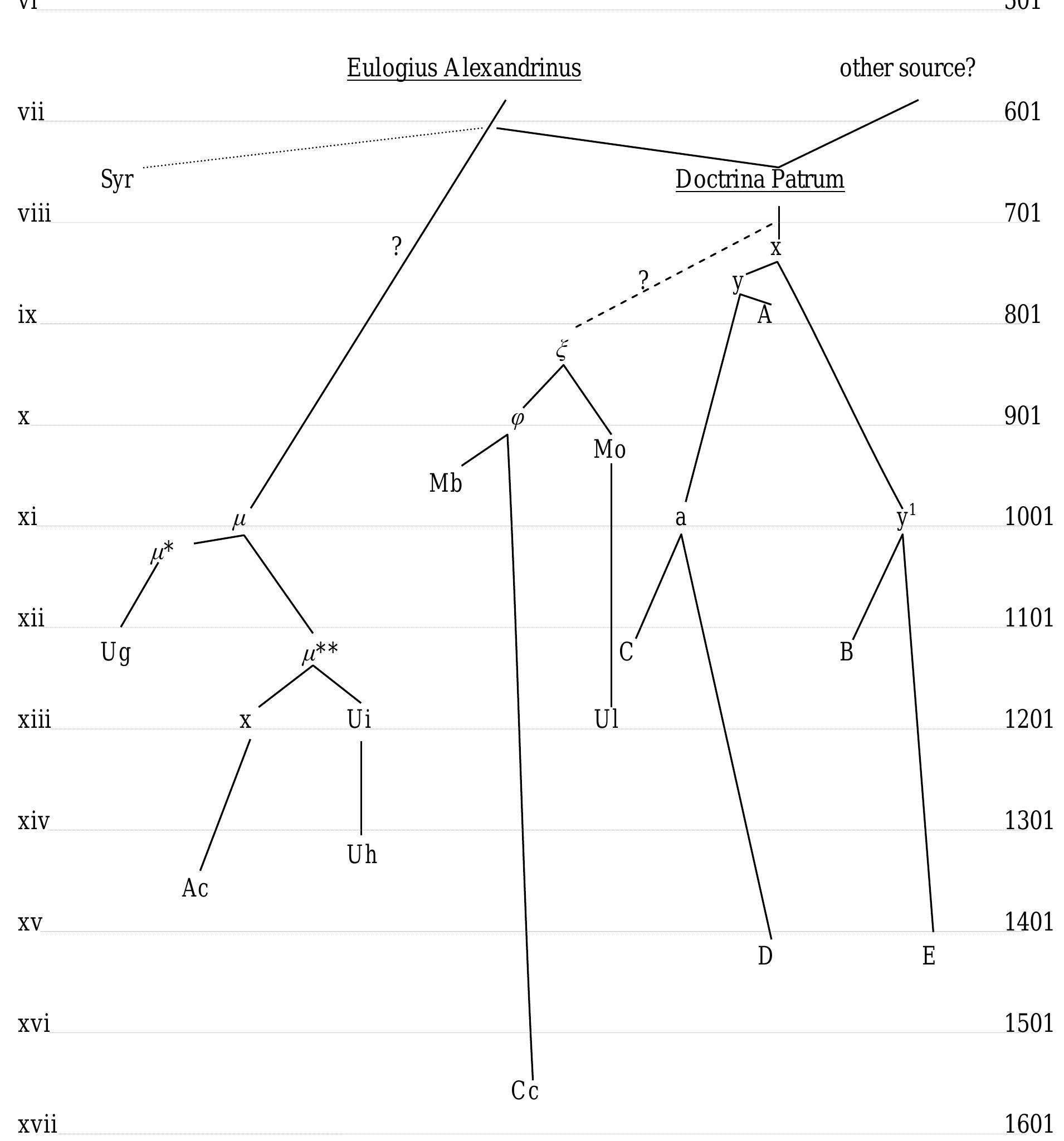

We start from the stemma built by Franz Diekamp, the editor of the Doctrina Patrum:48

x

y y1

a A B E

C D

The following variants in our text confirm it – we only list the faults and variants proper to a, y, y1 and

x, kindly referring the reader to the critical apparatus for those proper to the different mss. –:

— The existence of a is proved by some admittedly not very decisive faults common to C and D:

( ʹ) 4 ( π for π [coincidentally also in Mo]); ( ʹ) 5 ( φ' for φ'); ( ʹ) 3 ( π ῖα for π α)

and ( ʹ) 3 ( for )

— For y our collations provide no textual evidence, neither pro nor contra, but an extratextual

indication is the presence in the three mss. concerned of Leontius Byzantinus' Triginta capita contra

Severum [CPG 6814].49

— For y1 then we can refer to the following faults B and E have in common:

(ϛʹ) 4/5 (om. of π – , omission which the scribe of DPatr(B) has tried to correct by writing

φ ); ( ʹ) 1 ( for ); ( ʹ) 5 ( for [coincidentally also in Mb Cc Mo]) and ( ʹ)

6 (om. of ῖ π π ῖ )

— Valuable proof for the existence of x are, besides some small variants, four omissions common to

all five Doctrina Patrum mss.:

( ʹ) (5/6 om. of φ – α ); (ϛʹ) 1/2 (om. of π – 1

); ( ʹ) 2 (om. of π – πα 2

[coincidentally also in Mo]) and ( ʹ) 4 (om. of πα – πα 2)

1.2.2 Outside the Doctrina Patrum: Mb Cc Mo Ul

Finally, D.O.12 is also transmitted by four mss., viz. Mb Cc Mo and Ul, which neither as concerns their

contents, nor as concerns the text of D.O.12 show a clear relationship with the Doctrina Patrum: they

have none of the faults and variants typical of x. They share some admittedly not very decisive, faults and

variants:

( ʹ) 1 om. of α 2 [coincidentally also in DPatr(A)]

( ʹ) 5 for [coincidentally also in DPatr(BE)]

48 Cf. F. Diekamp – B. Phanourgakis – E. Chrysos, Doctrina Patrum de incarnatione Verbi. Ein griechisches Florilegium aus der

Wende des 7. und 8. Jahrhunderts, Münster 19812, p. XLIV.

49 In A this text is found as chapter 24, II, in C and D, however, as chapter 31.

11

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

We have called the hypothetical ms. responsible for this list . And although has hardly any readings

of its own, we have found no arguments to reject this hypothetical ms. either. In fact, in 1981 K.-H.

Uthemann edited what he called the 'antimonophysitische Aporien' of Anastasius of Sinai [CPG 7757], of

which the ms. tradition consists of these same four mss. He built the following stemma (we substitute his

sigla with ours):50

ξ

φ Mo

Mb Cc Ul

The evidence we have for D.O.12 will confirm Uthemann's stemma. In the following paragraphs we will

devote a bit more attention to these mss. than we have devoted to the other mss., as recent years have seen

some interesting new finds and publications.

Mb,51 dating from the second half of the tenth century,52 is on all accounts a very interesting ms. While

the place of origin is difficult to establish on palaeographical grounds,53 textually Mb is each time related

50 Cf. Uthemann, Aporien, cit., p. 19 (for the stemma).

51 On this ms., see A. Martini – D. Bassi, Catalogus codicum graecorum Bibliothecae Ambrosianae II, Milano 1906, pp. 767-780;

C. Pasini, Codici e frammenti greci dell'Ambrosiana. Integrazioni al Catalogo de Emidio Martini e Domenico Bassi, Roma 1997

(Testi e studi bizantino-neoellenici IX), pp. 83-87 and the doctoral dissertation by T. Fernández, Book Alpha of the Florilegium

Coislinianum: A Critical Edition with a Philological Introduction, Leuven 2010, pp. LXXVII-LXXX. Further bibliography can be

found in C. Pasini, Bibliografia dei manoscritti greci dell'Ambrosiana (1857–2006), Milano 2007 (Bibliotheca erudita: studi e

documenti di storia e filologia 30), pp. 306-307. The codicological characteristics of Mb are the following:

Membranaceus; 258 x 180 mm; 1 col.; 26-33 ll.; now 267 ff., but some folios are lost at the beginning (see below) and an

undeterminable number of folios is lost at the end; ff. 1-2 and ff. 266-267 were taken from a 13th-century Latin ms. containing a

Capitularium (for the details on these folios, see C.M. Mazzucchi, Un testimone della conoscenza del greco negli ordini

mendicanti verso la fine del Duecento (Ambr. Q 74 sup.) e un codice appartenuto al Sacro Convento di Assisi (Ambr. E 88 inf.),

« αῬ » 3, 2006, pp. 355-359); and both in the 29th and 32nd quire the second and third bifolios have switched places: the

correct order is ff. 220-219; ff. 224-223; ff. 244-243; ff. 248-247. There are 34 quires with the first quire number ʹ seen on f. 11

in the upper right-hand corner. With the exception of the 4th (ff. 19-23) and the 28th quire (ff. 208-217), all quires are

quaternions. As such probably one quaternion is lost at the beginning of the ms. Fortunately, the inner two bifolios of this quire

have recently been rediscovered by C. Pasini (Codici e frammenti, cit., p. 84 n. 4) as ff. 4-7 of Mediolanensis, Bibliothecae

Ambrosianae D137 suss. They contain an acephalous π α of the first part of our ms. (ff. 4-5v) and a π α of the second part, of

which, however, the end is lacking (ff. 5v-7v). For the ruling, see J. Leroy in H. Sautel, Répertoire de réglures dans les manuscrits

grecs sur parchemin, Turnhout 1995 (Bibliologia. Elementa ad librorum studia pertinentia 13), pp. 130, 110 and 304.

52 Similar scripts are found in Parisinus, Supplementi graeci 469A (a. 986) and Patmiacus graecus 138 (a. 988). We are not

entirely convinced of the correctness of Pasini's statement (Codici e frammenti, cit., p. 85 n. 6) that the ms. was probably copied

12

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

to mss. of a clearly Eastern Mediterranean origin. In the early 16th century Mb was found as number 317

in the collection of Cardinal Domenico Grimani (1461-1523).54 After Grimani's death his collection was

inherited by the Venetian monastery of S. Antonio di Castello, but already before 1528 Mb disappeared

from that library55 to resurface in the second half of the 16th century as part of the rich collection of books

and mss. of Gian Vincenzo Pinelli (1535-1601).56 In 1609, after 8 years of several people trying to get

hold of the precious library, 70 boxes full of books and mss. from Pinelli's library were bought by the

agents of Cardinal Federico Borromei (1564-1631) for the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana.57

The first part of the codex (ff. 3-131v) contains the third recension of the Florilegium Coislinianum.58

The second part (ff. 132-267v) is devoted to a large miscellany of dogmatic and philosophic nature, with

by at least two scribes. If so, their hands differ so very little that it has to be assumed that they were contemporaries and probably

worked together.

53 There are affinities both with Italian mss. and with mss. of the "tipo Efrem". On this last style of writing, see E. Follieri, La

minuscola libraria dei secoli IX e X, in La paléographie grecque et byzantine. Paris 21-25 octobre 1974, Paris 1977 (Colloques

internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique 559), p. 148 and n. 47. This article was reprinted in E. Follieri,

Byzantina et italograeca. Studi di filologia e di paleografia, Roma 1997 (Storia e Letteratura 195), pp. 205-248 (see p. 218 for the

relevant passage).

54 See the note on f. 4 of Mediolanensis, Bibliothecae Ambrosianae D 137 suss. (see footnote 51 above). The catalogue of the

Greek mss. and printed books in Grimani's library is preserved in Vaticanus, B.A.V., lat. 3960, ff. 1-13. It was probably made in

Rome before the move of the library to Venice in 1522. It has recently been edited by A. Diller – H.D. Saffrey – L.G. Westerink,

Bibliotheca Graeca Manuscripta Cardinalis Dominici Grimani (1461-1523), Mariano del Friuli 2004 (Biblioteca Nazionale

Marciana. Collana di Studi 1), pp. 107-165 (see p. 156, number 317 for Mb: "Sermones ecclesiastici diversorum").

55 For further details and proof we refer to the account by Pasini (Codici e frammenti, cit., pp. 85-86).

56 See the note on f. 2, upper margin: "J. V. Pinelli | Quaedam Theologica selecta, ut videre potes | in indice sequenti etc." On the

life of Gian Vincenzo Pinelli and the history of his library, see A. Rivolta, Catalogo dei Codici Pinelliani dell'Ambrosiana,

Milano 1933, pp. XVII-LXXX and more recently M. Grendler, A Greek Collection in Padua. The Library of Gian Vincenzo

Pinelli (1535-1601), «Renaissance Quarterly» 33, 1980, pp. 386-416. Some extra titles are found in A. Paredi – M. Rodella, Le

raccolte manoscritte e i primi fondi librari, in Storia dell'Ambrosiana. Il Seicento, Milano 1992, p. 85 n. 64, but they were not

accessible to us.

57 On this period after the death of Pinelli, on the auction of his library in 1609 and on the entry of the mss. in the Bibliotheca

Ambrosiana, see Grendler, Pinelli, cit., pp. 388-390 and Paredi – Rodella, Le raccolte manoscritte, cit., pp. 64-73.

58 The Institute of Palaeochristian and Byzantine Studies of the KULeuven is undertaking the edition of the Florilegium

Coislinianum. So far the following parts have been published or are in the process of being published – in alphabetical order of

the letters –: the letter A, by T. Fernández (forthcoming as volume 66 of the CCSG); the letter B, by I. De Vos – E. Gielen – C.

Macé – P. Van Deun, La lettre B du Florilège Coislin: editio princeps, «Byzantion» 80, 2010, pp. 72-120; the letter Γ, by I. De

Vos – E. Gielen – C. Macé – P. Van Deun, L'art de compiler à Byzance: la lettre Γ du Florilège Coislin, «Byzantion» 78, 2008,

pp. 159-223; the letter Η, by R. Ceulemans – I. De Vos – E. Gielen – P. Van Deun, La continuation de l'exploration du

Florilegium Coislinianum: la lettre èta, «Byzantion» 81, 2011, pp. 74-126; the letter , by R. Ceulemans – P. Van Deun – F.A.

Wildenboer, Questions sur les deux arbres du paradis: la lettre du Florilège Coislin, «Byzantion» 84, 2014, pp. 49-79; the

13

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

each text being numbered in the margin. Many of the texts are shortened, excerpted or adapted. The texts

relevant to this contribution, viz. D.O.12 and the lines from Eulogius' Adversus eos qui putant humanis

conceptionibus veram theologiam christianam posse subiici (see chapter 2 of this article), are found on f.

206r-v (number ϛ´) and ff. 251-252 (number ´) respectively.

The situation of Cc is quite different.59 The 600 years by which it postdates Mb do not result in more

information about its origin and possible peregrinations. On the contrary: we are completely in the dark.

The text it presents of D.O.12, however, is clear enough and a sufficiently large number of faults and

variants – some common to Mb Cc and some proper to each of them60 – confirm the stemma drawn by

Uthemann. A partial comparison of the contents of Mb and Cc may give an idea about the texts their

common ancestor, dubbed φ by us, must have contained:

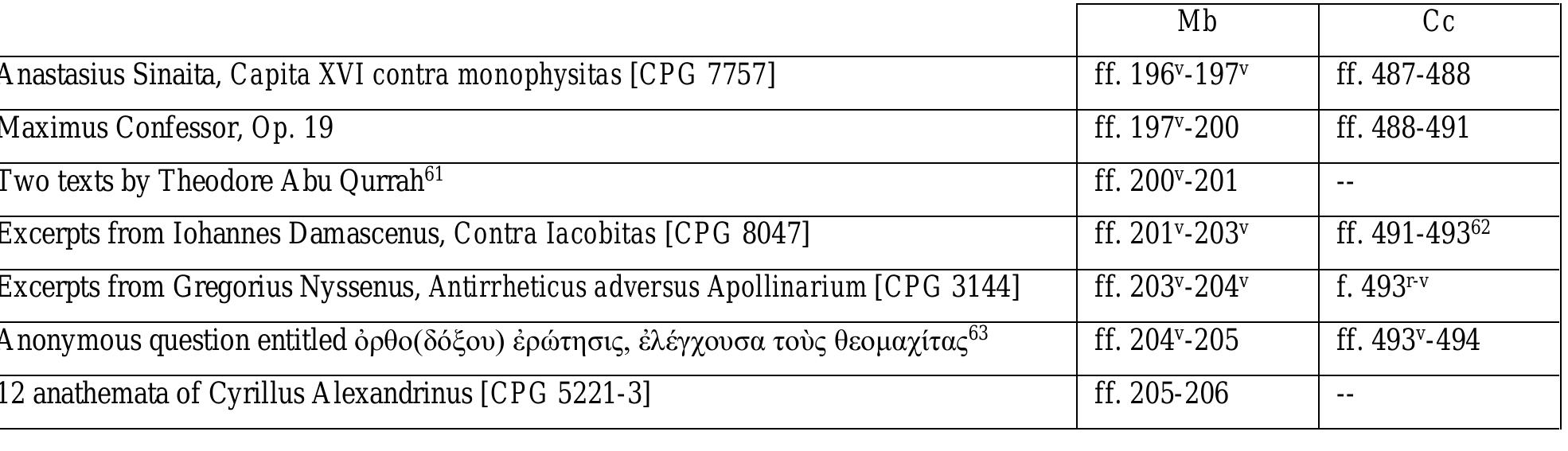

Mb Cc

Anastasius Sinaita, Capita XVI contra monophysitas [CPG 7757] ff. 196v-197v ff. 487-488

Maximus Confessor, Op. 19 ff. 197v-200 ff. 488-491

Two texts by Theodore Abu Qurrah61 ff. 200v-201 --

Excerpts from Iohannes Damascenus, Contra Iacobitas [CPG 8047] ff. 201v-203v ff. 491-49362

Excerpts from Gregorius Nyssenus, Antirrheticus adversus Apollinarium [CPG 3144] ff. 203v-204v f. 493r-v

Anonymous question entitled Χ υΨΝ ,Ν υ αΝ Ν α α 63 ff. 204v-205 ff. 493v-494

12 anathemata of Cyrillus Alexandrinus [CPG 5221-3] ff. 205-206 --

letter by R. Ceulemans – E. De Ridder – K. Levrie – P. Van Deun, Sur le mensonge, l'ame de l'homme et les faux prophètes: la

lettre Ψ du Florilège Coislin, «Byzantion» 83, 2013, pp. 49-82. At the moment R. Ceulemans, P. Van Deun and S. Van Pee are

preparing the edition of the letter Θ, while J. Maksimczuk recently started on a project of four years to edit the letters and .

References to older studies of this florilegium can be found in the introductions to these partial editions.

59 A description of Cc can be found in the catalogue by A. Papadopoulos-Kerameus, υ ἤ α

ῶ αῖ α ῦ ω υ π ῦ α α ῦ ὀ υ πα α χ ῦ υ ῶ ω α

π α α π ω ῶ ω ω IV, Sankt-Peterburg 1899, pp. 126-134. The codicological characteristics of

the ms. are the following: chartaceus, except for ff. 544-551: 14th-century bombycinus; 216 x 150 mm; 1 col.; 27-28 ll.; 610 ff.;

no quire numbers visible on our microfilm, which unfortunately, however, is of bad quality.

60 For the faults and variants that characterize Mb and Cc, please refer to the critical apparatus. The faults and variants they share,

are the following: Tit. –1 παπ for Ἐπαπ υ; Txt. – (αʹ) 3 α φ for φ ; ( ʹ) 1

add. of after ; ( ʹ) 1/2 for ; ( ʹ) 2 om. of υ πα π π υ (coincidentally also in Ug

Ac Ui); (ϛʹ) 1 and 2 α for ; ( ʹ) 4 α for (coincidentally also in DPatr(B)); ( ʹ) 3/4 α π

for α – ; ( ʹ) 4 , α for α ; ( ʹ) 6 α π ῖ α in Mba. corr. and α π ῖ in Cc for π π ῖ .

61 I.e. Opusculum 5 (PG XCVII, coll. 1521C-1524A) (f. 200v) and an apparently unedited text by Theodore, entitled α

π π υ υ α α υπ and with the incipit α αφ α ... (ff.

200v-201).

62 Cc is not mentioned in the edition of this text by Kotter, Johannes von Damaskos IV, cit., pp. 99-153.

63 This is a corruption of πα α.

14

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

D.O.12 f. 206r-v ff. 494-495

Mo dates from the same century as Mb. It was finished in April of the year 6440 A.M., i.e. 932 A.D.,

the 5th year of the indiction by the deacon Stylianus for Arethas, the famous Archbishop of the

Cappadocian Caesarea. How the ms. arrived in the Dionysiou monastery on Mount Athos is unclear, but it

was from there that in the middle of the 17th century the ms. was conveyed to Moscow.64 Despite its

venerable age, Mo is not entirely trustworthy: it has a remarkably large number of readings of its own.65

The Fettaugenstil of Ul, finally, is a typical product of the late 13th, early 14th century.66 There are

some indications that already in 1516 the ms. was found in the Vatican Library.67 According to Uthemann,

64 For further details on this ms., see Vladimir Filantropov, і М

( і ) і , Ча ь I. і , Moscow 1894, pp. 296-301; B.L. ἔὁὀkič – F.B. Poljakov,

М . ,

(Ф ), Moscow 1993, pp. 83-84; L.G. Westerink, Marginalia by Arethas in

Moscow Greek 231, «Byzantion» 42, 1972, pp. 196-244 (reprinted in Id., Texts and Studies in Neoplatonism and Byzantine

Literature. Collected Studies, Amsterdam 1980, pp. 295-343); L. Perria, Arethaea II. Impaginazione e scrittura nei codici di

Areta, «Rivista di Studi Bizantini e Neoellenici» n.s. 27, 1990, pp. 66-67, 68, 69 and 72 and P. Van Deun, Une collection

inconnue de questions et réponses traitant du trithéisme: étude et édition, «Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik» 51,

2001, pp. 105-106. The 25 anti-Judaic capita on ff. 83v-86 were edited by V. Déroche, La polémique anti-judaïque au VIe et au

VIIe siècle. Un mémento inédit, les Kephalaia, «Travaux et Mémoires» 11, 1991, pp. 275-311 (text: pp. 299-304; French

translation: pp. 304-307. This article is reprinted in G. Dagron – V. Déroche, Juifs et chrétiens en Orient byzantin, Paris 2010

[Bilans de recherche 5], pp. 275-311) and discussed by the same in Les dialogues adversus Iudaeos face aux genres parallèles, in

S. Morlet – O. Munnich – B. Pouderon (edd.), Les dialogues adversus Iudaeos. Permanences et mutations d'une tradition

polémique. Actes du colloque international organisé les 7 et 8 décembre 2011 à l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, Paris 2013

(Collection des Etudes Augustiniennes. Série Antiquité 196), pp. 257-266.

65 Please refer to the apparatus criticus of our edition.

66 Not catalogued as yet; K.-H. Uthemann, Anastasii Sinaitae Viae dux, Turnhout – Leuven 1981 (CCSG 8), pp. LX and CII-CVI;

Uthemann, Syllogistik, cit., pp. 108-109 n. 25 and almost identically in id., Aporien, cit., p. 17 n. 38; P.J. Fedwick, Bibliotheca

Basiliana Universalis II, 1, Turnhout 1996 (Corpus Christianorum), p. 350. Further bibliography is listed in P. Canart – V. Peri,

Sussidi bibliografici per i manoscritti greci della Biblioteca Vaticana, Città del Vaticano 1970 (ST 261), p. 536; M. Buonocore,

Bibliografia dei fondi manoscritti della Biblioteca Vaticana (1968-1980), Città del Vaticano 1986 (ST 318-319), p. 871; M.

Ceresa, Bibliografia dei fondi manoscritti della Biblioteca Vaticana (1981–1985), Città del Vaticano 1991 (ST 342), p. 366; M.

Ceresa, Bibliografia dei fondi manoscritti della Biblioteca Vaticana (1986–1990), Città del Vaticano 1998 (ST 379), p. 441 and

M. Ceresa, Bibliografia dei fondi manoscritti della Biblioteca Vaticana (1991–2000), Città del Vaticano 2005 (ST 426), p. 323.

67 Ul is mentioned as "Anastasii disputationes contra hereticos in gilbo ex papyro" in the list made by Romolo Mammacino

d'Arezzo shortly after September 1516 of the mss. bound in the Vaticana by librarian Thomas Inghirami. See the edition of this

list by R. Devreesse, Le fonds grec de la Bibliothèque Vaticane des origines à Paul V, Città del Vaticano, 1965 (ST 244), p. 184,

n. 70.

15

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

Ul was copied from Mo, a conclusion confirmed by our collations: on the one hand, Ul has all the readings

proper to Mo and at least partly a similar contents;68 on the other hand, Ul has a number of extra faults and

variants.69

Rather surprisingly, the evidence we have does not lead to the expected conclusion that is dependent on

a ms. of the Doctrina Patrum postdating their common ancestor x. Since as well as x have readings of

their own, they must go back to the same ancestor. In other words, via the Mb Cc Mo Ul branch it is

possible to go back to the time before x. Hence there are two possibilities.

Either x is nothing more than a copy of the Doctrina Patrum and was copied from the original

version or at least from a copy of the Doctrina Patrum preceding x:

DPatr

x

Or, independent from the question whether x is to be identified with the original version of Doctrina

Patrum or not, goes back to the text as it was found before it was inserted into the Doctrina Patrum:

D.O.12

DPatr(x)

It is unclear which of the two stemmata is the more probable – below we will draw the first one

without suggesting, however, that it is the correct one. As a matter of fact, an answer would be of little

consequence for our appreciation of the D.O.12. Even if it were true that goes back to a ms. of the

Doctrina Patrum preceding x (= first stemma) that would not exclude the possibility that D.O.12 existed

already before the compilation of the Doctrina Patrum.

68 Cf. Uthemann, Aporien, cit., p. 108 n. 25 and Westerink, Marginalia, cit., pp. 197-199. See especially the excerpts from Ps.

Iustinus martyr, Quaestiones Graecorum ad Christianos [CPG 1088] and Quaestiones Christianorum ad Graecos [CPG 1087],

the series of opuscula from Theodore Abu Qurrah and of course the presence of D.O.12, followed by Anastasius Sinaita, Capita

XVI contra monophysitas [CPG 7757].

69 The following list is exhaustive: ( ʹ) 4 (om. of ); ( ʹ) 4 (π φυ α for α π φυ [coincidentally also in

DPatr(B)]); ( ʹ) 8 (om. of π ); ( ʹ) 1 (add. ut videtur of after ); ( ʹ) 4 (om. through Augensprung of πα – πα 2

[coincidentally also in DPatr(ABCDE)]); ( ʹ) 1/2 ( ῖα for ῖ α ); ( ʹ) 5 (unlike

2).

Mo, Ul does not omit the preposition

16

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

1.3 The final stemma

The stemma of both versions together should in all probability look like this.

vi 501

Eulogius Alexandrinus other source?

vii 601

Syr Doctrina Patrum

viii 701

? x

? y

ix A 801

x φ 901

Mo

Mb

xi a y1 1001

*

xii 1101

Ug ** C B

xiii x Ui Ul 1201

xiv 1301

Uh

Ac

xv 1401

D E

xvi 1501

Cc

xvii 1601

After having collated all extant witnesses, it is clear that D.O.7 and D.O.12 differ considerably less than a

comparison between the text in the PG and the text in the Doctrina Patrum suggests. Indeed, if one

corrects the text of the PG with the help of Syr and the text in the Doctrina Patrum with the help of Mb Cc

17

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

Mo Ul, only three significant differences remain: the middle part of ( ʹ), the different wording in ( ʹ) and

of course capita ( ʹ) – ( ʹ).

1.4 Indirect tradition

Capita ( ʹ) 1/3, ( ʹ) 1/2 and ( ʹ) 1/3 of D.O.12 were used by Euthymius Zygadenus in his Panoplia

dogmatica, in Titulus XXIII α Ἀ (cf. PG CXXX, col. 1176B6-9, B10-12 and C1-4

respectively). We quote the text as it is found in the Patrologia Graeca:70

αφ υ, α α α , α φ υ, α πα ·π

αφ πα , α υ, α α ν

α φ , υ υ φ πα , π α

πα ν

α π ῖ α, α φ , , α

α π ·π φ ,α α π ν

It is unclear which ms. of D.O.12 was used by Zygadenus, although it would come as no surprise if he

used a copy of the Doctrina Patrum.

In the 14th century Neophytus Prodromenus excerpted Zygadenus for his Quaestiones et

Responsiones. The changes to Zygadenus' text of the Dubitationes Orthodoxi are minor:71

αφ Θ α υ α α α ,ὡ ῖ έ α φ

, Θ υ

α α ,π αφ α α υ α α ; Ὅπ π . αφ

, υ υφ α ,π α α

; Θ α π ῖ α, α

φ , Θ , α α π ,π φ ,α Θ α π ;

1.5 The previous editions

1.5.1 The edition of D.O.7 by Fr. Combefis (pp. 145-146)

In his Elenchus operum sancti Maximi redacted in December 1660, i.e. 15 years before his edition,

Combefis wrote:72

70 A collation of the Panoplia mss. we had at our disposal, viz. Parisinus graecus 1232A (a. 1131), f. 163, Patmiacus graecus 103

(a. 1156/1157), f. 156v, Vaticanus graecus 668 (a. 1305/1306), f. 252 and Vaticanus, Palatinus graecus 200 (s. XII-XIII), f. 178v,

revealed hardly any variants. The second ms. omits the last α of the first caput. The third one omits in the third caput.

71 Neophytus' Quaestiones et responsiones were edited by . Kalogeropoulou-Metallinou, Ὁ αχ όφυ α

ό υἔ , Athens 1996, pp. 409-527. For the fragment quoted above, see Qu. et Resp. 2α, ll. 222-232 (p. 440). For

these lines the dependency on Zygadenus was overlooked by the editor. On Prodromenus, see also the article by M. Cacouros,

Néophytos Prodromènos copiste et responsable (?) de l'édition quadrivium-corpus aristotelicum du 14e siècle, «Revue des Études

Byzantines» 56, 1998, pp. 193-212.

72 The text of the Elenchus can be found in B. de Montfaucon, Bibliotheca Coisliniana, olim Segueriana; sive manuscriptorum

omnium Graecorum, quae in ea continentur, accurata descriptio, ubi operum singulorum notitia datur, aetas cuiusque

18

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

Capitula XV. dubitationum, de naturalibus voluntatibus & operationibus. Reg. Cod. extat. & Vat. DIV. ex

quo capitula alia XIII. de iisdem, Ὅ α .α : cum subjunctis definitionibus Clementis

Alexandrini, & Eulogii Patriarchae Alexandrini, capitula VII. Tum aliae XI. definitiones.

This clearly is a description of ff. 146ra-146vb of Ug: 73 subsequently, Combefis refers to Add. 19

("Capitula XV 74 . dubitationum, de naturalibus voluntatibus & operationibus"), Add. 18 ("capitula alia

XIII. de iisdem"), Op. 23a ("Ὅ α . α "), the fragment from Ps. Clement's De

providentia following Op. 23a in the PG ("cum subjunctis definitionibus Clementis Alexandrini"), Op.

23b ("& Eulogii Patriarchae Alexandrini, capitula VII") and Op. 23c ("Tum aliae XI. definitiones"). The

differences between his edition and the text in Ug are small ([ ʹ] 1 for ; [ ʹ] 2 for ; [ ʹ] 1 π

for π ), with the notable exception, however, of the reading φ for φ on line 8 of the third

chapter. This reading would suggest that Combefis used Ac, Ui or Uh for his edition. However, the change

of the nominative into the genitive is too easily made to allow for the conclusion that Combefis did not do

what he announced himself in his Elenchus.

J.-P. Migne reprinted Combefis' edition of Op. 23b twice, once amongst Maximus' writings (cf. PG

XCI, coll. 264D1-265C4) and once amongst the texts by Eulogius (cf. PG LXXXVI, coll. 2937C1-

2940C12). Both reprints are trustworthy, but not identical. In the former was changed into α ([αʹ]

1), a misinterpretation of the abbreviation for used in Combefis' edition, and α Θ was wrongly

omitted after υ υ in the title. In the latter the capita were numbered, as found in Combefis'

edition was corrected into ([ ʹ] 2) and was correctly changed into ([ ʹ] 2).

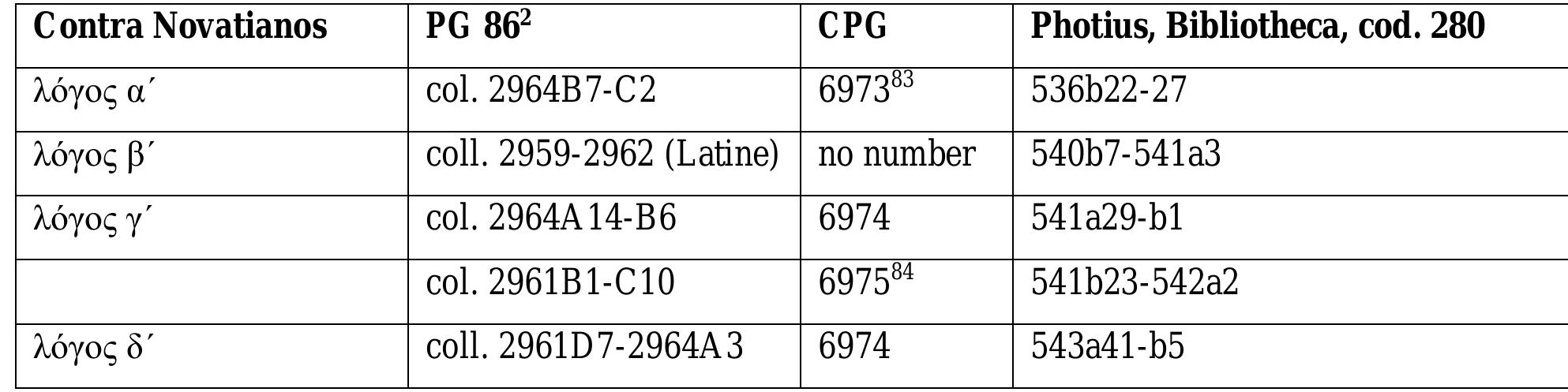

1.5.2 Diekamp's edition of the Doctrina Patrum

For his edition of D.O.12 in the context of the Doctrina Patrum 75 Diekamp collated the five mss.

which contain that florilegium. Moreover, he referred to the presence of Op. 23b in Mb, without however

using the ms.76 This is all the more pityful as a collation might have considerably improved the text as

found in the mss. of the Doctrina Patrum.

Manuscripti indicatur, vetustiorum specimina exhibentur, aliaque multa annotantur, quae ad Palaeographiam Graecam

pertinent, Parisiis 1715, p. 309. For more details on this Elenchus, see B. Janssens, François Combefis and the Edition of

Maximus the Confessor' Complete Works (Paris, 1675/1679), in «Analecta Bollandiana» 119, 2001, pp. 357-362.

73 For the "Reg. Cod." mentioned by Combefis, see the last paragraph of the present chapter 2.1.

74 The fact that the Elenchus mentions 15 capita for Add. 19 is probably due to a misprint. The description cannot refer to another

text, because no text with 15 chapters of dubitationes concerning the natural wills and operations is known to have been written

by Maximus and because the words "dubitationum, de naturalibus voluntatibus & operationibus" are a verbal translation of the

title of Add. 19 in Ug.

75 Cf. Diekamp, Doctrina Patrum, cit., p. 152, l. 15 – p. 155, l. 10.

76 Cf. the critical apparatus on p. 152 in Diekamp, Doctrina Patrum, cit. He only notes (cf. the apparatus fontium on p. 153) that

Mb wrote υ in the margin. However, this marginal note has nothing to do with Gregorius Nazianzenus as he thought –

19

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

His critical apparatus is concise, but mostly correct. Still, after double-checking the mss. we would like

to make the following additions and corrections – we first give the line number in our edition, then the line

number in Diekamp's edition –:

([ ʹ] 1; p. 153, l. 6) no indications of the problems with π φ in DPatr(D)

([ ʹ] 2; p. 153, l. 8) DPatr(C) does not read but for

([ ʹ] 5/6; p. 153, ll. 11/12) before the entry " π α bis mit Tilgungspunkten C" the line

numbers 11-12 should be added

([ ʹ] 5; p. 153, l. 21) the variant φ' for φ' in DPatr(CD) is not found in Diekamp's apparatus

([ ʹ] 3; p. 154, l. 5) the omission of in DPatr(C) is not mentioned by Diekamp

([ ʹ] 2; p. 154, l. 8) the reading ' in DPatr(B) for the reading ' as found in the other

Doctrina Patrum mss. is not mentioned by Diekamp

([ ʹ] 1; p. 154, l. 18) the fault for is only found in DPatr(BE), not in DPatr(A) as indicated by

Diekamp

([ ʹ] 3; p. 154, l. 20) DPatr(A) has , not and DPatr(E) has not instead of

1.6 Ratio edendi

In order to avoid having to print three quarters of the text and apparatus twice, the edition we present is

one of both versions at once and this has important consequences. On the one hand, because on several

occasions it is impossible to decide between one of the two versions, because it should be avoided to make

a mere mixture of both versions and because D.O.12 is the longest, we decided to choose the most

practical solution and present in principle the text of D.O.12. We are fully aware that this may seem in

contradiction with our conclusion that D.O.7 predates D.O.12. On the other hand, in the critical apparatus

we underlined the readings of D.O.7, so that the reader of our edition can easily get an idea of that version:

were underlined once, the readings common to Ug Ac Ui, but which are not found in Syr; were underlined

twice, the readings common to Ug Ac Ui and Syr.

The critical edition of this text is made with as much respect for the mss. as can be justified on the

basis of present-day scholarly standards. This has the following consequences:

punctuation: the mss. have been double-checked for the position of the punctuation marks. As a

result, every punctuation mark in our edition corresponds to a punctuation mark in the majority of

the mss., although no all punctuation marks have been preserved.

accentuation: special attention has been payed to the accentuation in the mss., which, as is well-

known, differs from the rules in school grammars.77 As such the reader will find πα , α

(even if is indefinite) or α φα . Moreover, since the use of a gravis before 'weak

Diekamp refers to Ep. 101, 4 (edd. P. Gallay – M. Jourjon, Grégoire de Nazianze, Lettres théologiques, Paris 1978 [SC 250], p.

38) –, but with the words υ ([ ʹ] 1), of which it probably is a correction or a variant reading.

77 See most recently J. Noret, L'accentuation byzantine: en quoi et pourquoi elle diffère de l'accentuation «savante» actuelle,

parfois absurde, in M. Hinterberger (ed.), The Language of Byzantine Learned Literature, Turnhout 2014 (Studies in Byzantine

Literature and Civilization 9), pp. 96-146.

20

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

punctuations' like a comma is quite common in mss. (and, as a matter of fact, quite justified), we

decided to preserve also this feature.78

apostrophe: except in fairly late mss., scribes rarely end a line with an apostrophe, and would

rather write ' -| than '| . It is a clear indication for the close

connection between the apostrophized word and the next word. Therefore, as in French or Italian,

we never added a space (or punctuation) after an apostrophe.

Ἐπαπ υπ α π α PG1 264D

PG2 2937C

π φ DPatr 152

αʹέΝ Νφ Ν Ν Ν Ν Ν Ν Ν

,Ν π π α ,Ν Ν α ,|Ν Ν φ νΝ α Ν ανΝ PG2 2940A

π υ Ν φ α ,Ν π Ν α,Ν Ν φ Ν αΝ π Ν

νΝ ,Νπ Ν Υ Ν Ν πα ,Ν υ υΝ

5 π ν|

ʹέΝ π Ν Νφ Ν Ν ῖ α ,Ν π Ν υ α Ν Ν DPatr 153

Ν Ν Ν Ν ,Ν α Ν Ν |Ν νΝ PG1 265A

ῖ αΝ Ν Νφ Ν α ,Ν π π Ν Ν Νφ Ν

,Ν α Νπ Ν Ν έ

ʹέΝὉ Ν Ν Ν π φ α , νΝἈ Υ

Ν ,Ν π Ν Ν Ν ,Ν υΝ πα Ν

π π υνΝ Ν φυ Ν α Ν π Ν π Ν α Ν α Ν

α Ν Ν α Νπ φυ ,Ν α αῖ Ν π Ν αῖ Ν π Ν α

5 α Ν αφ α Ν Ν π α ·Ν φ Ν Νφ Ν

Ν π Ν α ,Ν Ν π Ν Ν

α ῖ α έΝ Ν Ν Ν Ν α ,Ν Ν α Ν π έΝ

Ν Ν υ,Νπ Ν Νφ Ν ν

ʹ. α φ υ α ῖ ῖ .

Ἀ ' α α υ α α ῖ

, π ῳ α ΐ π

α α ' α αυ ν φ α

5 φ' α , π α α α , α π ῖ ν

ʹέΝ αΝ φ Ν υΝ α Ν α ,Ν αΝ φ Ν

υΝ α πα ,Ν π Ν αΝ φ Ν πα Ν α υΝ α Ν

78 See e.g. S. Panteghini, La prassi interpuntiva nel Cod. Vind. Hist. gr. 8 (Nicephorus Callisti Xanthopulus, Historia

ecclesiastica): un tentativo di descrizione, in A. Giannouli – E. Schiffer (edd.), From Manuscripts to Books. Proceedings of the

International Workshop on Textual Criticism and Editorial Practice for Byzantine Texts (Vienna, 10–11 December 2009), Wien

2011 (Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse. Denkschriften, 431. Band), p. 142:

"Anzi, parrebbe in molti casi che la scelta dell'accento discenda da una percezione del grado d'indipendenza di un

all'interno della superiore gerarchia sintattica: si dipende da un verbo finito che si trova altrove – o nell'enunciato principale o nel

successivo –, o se è in relazione stretta con elementi che lo circondano, la non determina quel grado di indipendenza

che le consente di impedire la baritonesi."

21

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

α ν

ϛʹέΝ α Υ Ν Ν Ν Ν α ,Νπ Ν α π αΝ Ν Ν

Ν α νΝ α α π αΝ Ν Ν Ν α ,Ν π Ν Ν

αΝ Ν ,Ν α Ν ,Ν α ΐ Ν π Ν α |Ν πα DPatr 154

Ν Ν νΝ α π αΝ Ν Ν Ν α ,Νπ Ν

5 α Ν Ν Ν α ν

ʹέΝ α Νπ Ν αΝ Ν Ν Ν α Ν α,Ν αΝ

Ν Ν α πα ,Νπ Ν Ν Ν Ν Ν α πα ,Ν α

Ν ,Ν Ν Ν Ν α ,Ν α Υ Ν Ν ν

ʹέΝ Ν Νφ Ν αΝφ Ν Ν Ν Νφα ,Ν πα Ν Ν

Ν έΝ α Ν Ν α αΝ ,Ν φ Ν Ν αΝ

πα Ν Ν Ν ,Ν πα Ν π αΝ α ,Ν α Ν α Νφ Ν

αΝ έΝ Ἀ Ν Ν Ν α Νφ ,Ν α α αΝ

5 έ

ʹέΝ αΝφ Ν Ν Ν Ν ,Ν Ν υ υΝ

φ Ν πα ,Νπ Ν α Ν Ν πα Ν Ν νΝ

α Ν α Ν Ν αυ φ Ν Ν Ν Ν

πα ,Ν πα Ν α π α Ν φ Ν Να Ν Ν πα ,Ν α

5 α Υ Ν α ῖ Ν ,Ν α Υ έ

ʹέΝ Ν α π Ν α α Υ Ν Ν Ν Ν

ῖ α ,Ν α φ Ν Ν Ν α α π ,Νπ Ν

Νφ ,Ν Ν α π Ν ν

αʹέΝ υ Ν α Ν Ν Ν α υΝ α Να

φ ,Ν ῖ αΝ α Ν αφ Ν Ν α Ν α ,Ν

π Ν Ν Ν Ν Νφ Ν Ν Ν Ν

αφ έΝ Ν α φ Ν α ,Ν α Ν αφ

5 α α ,Ν Ν υ αΝ π Ν π νΝ αφ Ν Ν αΝ

Νπ α ·Νπ Ν Ν Ν α α αφ Ν αυ νΝ

Ἀ Ν Νπ Ν Ν|Ν Ν αφ Ν π Ν π ῖ Ν Ν αφ ,Ν DPatr 155

αΝ Ν α ππ α Ν φ Ν Ν Ν αφ έ

ʹέΝ Ν Ν α π Ν Ν Ν Ν υ ῖ α ,Ν

α φ Ν ῖ Ν Ν Ν Ν α π Ν Ν α Ν Ν

φ Ν Ν ,Ν Ν Ν Ν Ν α π Ν Ν

Ν α ,Ν Ν Νφ Να Ν Ν ῖ ,Ν

5 π π α Ν α Υ π Ν Ν Ν Ν α Ν π Ν

Ν ῖ Νπ π ῖ ν

— Apparatus fontium et locorum parallelorum

αʹ. 3/5 ( – π ) cf. Leont. Byz., Triginta Cap. [CPG 6814] 19 (ed. Diekamp, Doctrina Patrum, cit., p. 158, l. 34 –

p. 159, l. 1); Leont. Hierosol., C. Monophys. [CPG 6917] 36 (PG LXXXVI, col. 1792B12-14); Probus, Syllog. adv. Iacob. (gr.) 4

(ed. J.H. Declerck, Probus, l'ex-jacobite et ses Ἐπαπ ααπ α ω α , «Byzantion» 53 [1983], ll. 14-17 [p. 230]); Leont.

mon. Pal., Syllog. adv. Iacob. (syr.) 3 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 26, l. 25 – p. 27, l. 1; [transl.], cit., p. 18, ll. 31-32); Op.

Chalc. anon. VIII, 4 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 18, ll. 9-14; [transl.], cit., p. 13, ll. 10-14)

22

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

ʹ. 1/2 (Ὁ – ) Probus, Syllog. adv. Iacob. (syr.) 19 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 12, l. 30 – p. 13, l. 1;

[transl.], cit., p. 9, ll. 24-26) 7/8 ( – ν) cf. Ioh. Gramm., C. Monophys. [CPG 6856] 15, ll. 150-151 (ed. Richard,

Iohannes Caesariensis, cit., p. 65; = Anast. Sin., C. Monophys. [CPG 7757] 1, ll. 7-8 [ed. Uthemann, Aporien, cit., p. 23]);

Probus, Syllog. adv. Iacob. (syr.) 19 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 13, ll. 1-3; [transl.], cit., p. 9, ll. 26-27)

ʹ. 1 ( α – α ) A Leont. Hierosol., C. Monophys. [CPG 6917] (PG LXXXVI, col. 1809B14-C3) ad Arium et

ad Apollinarium attributum (cf. Apollin. Laod., Ep. ad Iov. [CPG 3665] [ed. H. Lietzmann, Apollinaris von Laodicea und seine

Schule I, Tübingen 1904, p. 251, ll. 1-2; vide et in Diekamp, Doctrina Patrum, cit., 9, XI, p. 62, ll. 15-16]), sed praesertim apud

Cyrill. Alex., e.g. C. Nestorianos [CPG 5217] II prooem. (ed. ACO I, 1, 6, p. 33, ll. 6-7) vel Ep. 45 [CPG 5345] (ed. ACO I, 1, 6,

p. 153, l. 23). Vide A. Grillmeier, Jesus der Christus im Glauben der Kirche, Band 1, Von der Apostolischen Zeit bis zum Konzil

von Chalcedon (451), Freiburg – Basel – Wien 19903 (2004), p. 674, n. 2 2/4 (Ἀ ' – αυ ) Greg. Naz., Ep. 101 [CPG

3032], 19-20 (ed. Gallay – Jourjon, Lettres théologiques, cit., p. 44); Ioh. Gramm., C. Monophys. 2, ll. 31-36 (ed. Richard,

Iohannes Caesariensis, cit., pp. 61-62); Ioh. Gramm., Apol. conc. Chalc. [CPG 6855] ll. 242-245 (ed. Richard, Iohannes

Caesariensis, cit., p. 57)

ʹ. 1/3 ( – α ν) Cf. Ps. Quintian., Ep. ad Petr. Full. [CPG 6525] 3 (ed. ACO III, p. 15, ll. 18-20 [coll. Sabb.]; p. 227, ll.

27-28 [coll. antiq.]); Ioh. Gramm., C. Monophys. [CPG 6856] 2, ll. 29-31 (ed. Richard, Iohannes Caesariensis, cit., p. 61); Anast.

monach. (Antioch.?), C. Monophys. (syr.) 11 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 30, ll. 12-17; [transl.], cit., p. 21, ll. 11-15);

Probus, Syllog. adv. Iacob. (syr.) 7 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 9, ll. 9-14; [transl.], cit., p. 6, ll. 30-34); Op. Chalc. anon.

II, 3 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 2, ll. 16-21; [transl.], cit., p. 2, ll. 8-13); Op. Chalc. anon. XII, 15 (ed. Bettiolo, Una

raccolta [ed.], p. 36, ll. 12-17; [transl.], cit., p. 25, l. 31 – p. 26, l. 5)

ϛʹ. 1/5 ( – ν) Cap. syllog. (in cod. Vat. gr. 2220, ff. 83-84v), 2, ll. 5-12 (ed. Uthemann, Syllogistik, cit., p. 111)

ʹ. 1/2 ( – ) vide supra ad caput αʹ, ll. 3/4

ʹ. 1/3 ( – ) Leont. Byz., Triginta Cap. [CPG 6814] 20 (ed. Diekamp, Doctrina Patrum, cit., p. 159, ll. 15-19)

αʹ. 1/8 ( – αφ ) Cf. Leont. mon. Pal., Syllog. adv. Iacob. (syr.) 6 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 27, ll. 16-20;

[transl.], cit., p. 19, ll. 11-14); Op. Chalc. anon. XII, 2 (ed. Bettiolo, Una raccolta [ed.], p. 33, ll. 11-18; [transl.], cit., p. 23, ll. 15-

21) 1/2 ( υ – α α φ ) Cyrill. Alex., Scholia 11 [CPG 5225] (ed. ACO I, 5, p. 190, 28 [lat.]; p. 227, l. 12

[fragm. gr.]) 2( ῖα – α ) Symb. Chalc. (ed. ACO II, 1, 2, p. 129, ll. 31-32) 6 (π ... ;) Anast. I

Antioch., Dialogus [CPG 6958] 614 (ed. Uthemann, Streitgespräch, cit., p. 98)

ʹ. 1/6 ( – π π ῖ ) cf. Leont. Byz., Triginta Cap. [CPG 6814] 3 (ed. Diekamp, Doctrina Patrum, cit., p. 155, ll. 24-

28); Anast. I Antioch., Dialogus [CPG 6958] 475-478 (ed. Uthemann, Streitgespräch, cit., p. 94)

— Sigla et Apparatus criticus

Tit. 1/2 Ἐπαπ – φ ] α α υ υ π πα α α φ αα π ( Ac Ui) π

φ υ υ α Ug Ac Ui; π α απ υ α α φ υ

. φ αα ´ Mo; ܒܥܐΝܕܦ ܩܐΝܐܐ Νέ'( ܬ ܒ · π π Φ π ') Syr 1

Ἐπαπ υ] παπ Mb Cc; παπ α DPatr(B); παπ υ DPatr(CE);

πα υ DPatr(D)

αʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1 αʹ]Ν ܩܕܚܝܐΝ '( ܐܐπαπ Νπ ΥΨ Syr Νφ ]Ν ܟܝܢܐΝ ܚܕΧΥ αΝφ ΥΨ Syr 1/2 – ] inv.

ord. Syr 1 2]

om. DPatr(E), Cc, Ug Ac Ui 2 π α ] Ν ܐܝܢܐΧΥπ αΥΨΝSyr 3 ] ' DPatr(E) φ α] φ α Ac

] Mo φ ] α φ Mb Cc α π ] α π DPatr(C); π α Mo 4 ']

DPatr(E) 4/5 – π ] ut partem capitis ʹ scripsit Cc

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1 ] add. Mb Cc φ ] ܟܝ ܐΝ ܬܪܝΧΥ Νφ ΥΨ Syr ] add. Ug Ac Ui, Syr ῖ α]

α DPatr(B); α et add. Ug Ac Ui, Syr 1/2 ] inv. ord. Mb Cc, Syr 2 ] '( ܚܕα ') Syr

23

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

] om. Mo α ] om. Syr 3 ῖ α] α DPatr(ABE), Ug Ac Ui ] om. Mo

φ 1] ܟܝ ܐΝ '( ܬܪܝ φ ') Syr φ ] φ Ug Ac Ui φ 2] ܬܪܝΝ'( ܟܝ ܐ φ ') Syr

4 π ] π DPatr(CD), Mo ] om. Mb Cc; a. (l. 4) trps. Ug Ac Ui ] ܟܝܢܐΝ '( ܚܕα φ ') Syr

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1. ] om. Mb π φ ]π φ (sic) DPatr(Da. corr.); π φ DPatr(Dp. corr.); πα 'α φ Ug Ac

Ui, Syr 2 ] DPatr(C); Cc υ–π π υ] υπ π υ πα DPatr(D); om. Mb Cc, Ug Ac Ui,

Syr 3/7 – π ] om. Ug Ac Ui, Syr 3/4 α – ] α α Cc; α Moa. corr.;

α φ Mo p. corr. in marg. 4 α π φυ ] π φυ α DPatr(B) αῖ – αῖ ] αῖ π αῖ (sic)

DPatr(C) π ] supra l. add. DPatr(C) 5 1] om. Mb 5/6 π α – ] expunxit DPatr(C) 5 π α]

π Cc; π α Mo 5/6 φ – α ] om. DPatr(ABCDE) 5 φ ] om. Mo 6 ] α DPatr(Bp. corr. a

manu recentiore) 7 ] DPatr(E) α] Cc; α Mo 8 ] α add. DPatr(ABCDE); bis scripsit Cc

υ] ܡܠܬܐΝ'( ܐ ܐ ῳ') Syr ] Mo φ ]φ Cc, Ac Ui

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1 υ] ( υ) Mbp. corr. in margine ut videtur ῖ ῖ ] ῖ ῖ α DPatr(D);

ῖ ῖ Mo; φα (φα Ac Ui; ܐܒ ܬܐΝ '[ ܐܡ ܝφα πα '] Syr). α α

Ug Ac Ui, Syr 2 α α ] α Ug Ac Ui; ܐܝܬܝΝܐ ܝܐΝܕܚܕܐΝ Ν '( ܐܝ α ') Syr, cf. et l. 4

υ] om. Ug Ac Ui 2/3 – ] ῖ DPatr(B); ῖ α

DPatr(Da. corr. ); ῖ α Mb a. corr. ; υ α add. Mo; Ug Ac Ui; ܐ ܬܟܠΝ ܕܐ

(' ') Syr 3π ]π α DPatr(D); α Mo 1 – ῳ] ܐ Νܒ ܝܐΝܒ ܝܐΝܐΝ ('

α ') Syr 1] DPatr(Da. corr. ) α ] om. Mo, Syr 2 ] Mb 4 α' α ] om. Ug Ac Ui 5 φ'] φ'

DPatr(CD) ] om. Ug Ac Ui, Syr ] Mo π ῖ ] om. Mo

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1/2 – α 1] om. Ug Ac Ui 2 π – πα 2] om. Mo πα 2 – υ2] υ α πα Ug Ac Ui α 3]

om. Mb a. corr. ; α praem. Mo

ϛʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1 α '] '( ܐܦα ') Syr 1/2 π – 1] om. DPatr(ABCDE) 1 π α] om. Mba. corr. ] α Mb Cc (cf. l. 2) 2 α –

2] in marg. DPatr(D) – 2] om. Mo ] α Mb Cc (cf. l. 1) 3 α ] om. Syr 3/4 ΐ – ]

υ αΐ πα α Ug Ac Ui 3 πα ] ܐܒܐΝ'( ܐ ܐ πα ') Syr 4 ] '( ܐܦα ') add. Syr 1 ]

om. DPatr(ABCD) 1] praem. Ug Ac Ui; '( ܐ ܐ ') add. Syr ] , DPatr(E) α 1] α (sic) DPatr(A)

] om. Cc 4/5 π – ] φ DPatr(B); om. DPatr(E) 5 α ] correxi e α Ug Ac Ui, cf. ( ʹ) 2;

DPatr(AC), Mb; DPatr(D); Cc; Ν Mo; ܡܕܡΝ ܚܕ... (' – ') Syr 5 ] DPatr(Aa. corr.)

α ] om. Cca. corr.

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo, Ug Ac Ui, Syr

1 ] addidi e Ug Ac Ui, Syr; om. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo ] α ' sic Mout videtur; '( ܝܬܝπ ') praem. Syr 2 π

– πα 2 ] om. DPatr(ABCDE), Mo ] (sic) Cc ] om. Ug Ac Ui; p. (l. 2) trps. Syr 2/3 3 – α ] om.

2] '( ܠ

Ug Ac Ui – ] fenestram habet Cc 3 ] om. DPatr(C) α '] - (' α ') praem. Syr ') add. Syr

Scripsit Arethas CaesarἑensἑsΝ ἑnΝ marРἑneΝ codἑcἑsΝ εo,Ν П.Ν 10ζ,Ν adΝ caputΝ ʹ, haec verba (cf. et Westerink, Marginalia, cit., p.

227): φ υ π πα α, α υπ α, ῖα α α φ

ῖ α ῖ

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo

1φ ] om. DPatr(D) 2 ] om. Cc Mo ] (sic) DPatr(Cut videtur); Mo ] '

DPatr(ACDE), Mo; ' DPatr(B) 3 ] DPatr(E) ] Mo ]Νom. DPatr(E)

π α] π ῖα DPatr(CD); π ῖα Mo α φ ] Mo 4 α] Mo, DPatr(Aa. corr.) ] α

DPatr(B), Mb Cc; DPatr(C); Mo α ] α Cc α ] fenestram habet DPatr(D)

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo

24

�Bram Roosen – Eulogii Alexandrini quae supersunt

1 ] DPatr(Aa. corr.) 1/2 υ υφ ]φ υ υ Mo 3 ] om. Mo –φ ]

α αυ φ add. DPatr(B); α φ Mo ] α DPatr(BDa. corr.), Cc 4 πα – πα 2] om.

DPatr(ABCDE) φ α ]α φ Mo 5 ] DPatr(D) α ῖ ] supra l. add. Mb α ] om.

DPatr(E) ] Mb α '] α DPatr(B), Mo

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo

1 α 2] om. DPatr(A), Mb Cc Mo α ' ] Ν α Υ ΝMo ] DPatr(BE) 2 ῖ α]

ῖ DPatr(A), Cc; α DPatr(B) ] DPatr(B); Cc α ]α Mba. corr. ] Cc 3 ]

DPatr(A); DPatr(CD); DPatr(E); Mba. corr.; Cc; om. Mo ] Mo

αʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo

3 ] om. Mo 4 – αφ ] bis scripsit Cc 6 αφ ] αφ Mo αυ ]α DPatr(B) 7 π ῖ ]

π ῖ Mo 8 ] om. Cc

ʹ. DPatr(ABCDE), Mb Cc Mo

1 ] α DPatr(BD), Mb υ ῖ α] υ α Mo 2 φ ] φ DPatr(B), Mo α

π ] om. Cca. corr. 2/3 α 3 – φ ] expunxit DPatr(C) 3 ] DPatr(BDa. corr.) ]

DPatr(D) 3/4 α – ] α π Mb Ccp. corr.; om. Cca. corr. 4 α] , α Mb Cc

ῖ ] praem. DPatr(C) 5 ] DPatr(BE), Mb Cc Mo 2] om. Mb Mo 6 2] om. Mo ῖ

π π ῖ ] om. DPatr(BE) π π ῖ ] α π ῖ α Mba. corr.; π π ῖ α Mbp. corr.; α π ῖ Cc

Objections of an orthodox against those who advocate one nature

with regard to Christ

1. If ( ) after the union Our Lord Jesus Christ is of one nature, tell me of which ( π π α ). Of the

one that takes or of the one that is taken? And tell me what happened to the other nature? If however (

) both natures exist, how (π ) can there be one nature, unless ( ) one composite nature was made

out of both? But if ( ) so, how (π ') can Christ not be of a different essence with respect to the

Father, who is not composite?

2. If ( ) Christ is confessed to be never of two natures, how (π ) is it possible to state that Christ is of

one nature after the union, or even on the whole to say union? But if ( ) Christ is confessed to be of

two natures, tell me when ( π π ) Christ was of two natures, and from what time onwards ( π ) he

was of one nature.

3. Are the God Word and the flesh Ηe assumed of the same or of different essence? If ( ) they are

of the same essence, then how (π ) is it that the triad is not a tetrad, since another person is introduced

into it? For ( ) identity of nature and identity of essence are naturally predicated of individuals that

share the same essence, and identity of essence is said of individuals that share the same form ( ἶ ):

indeed ( ), one nature is never said to be of the same essence as another nature, but identity of essence

is predicated of individuals. Therefore ( ), if the God Word is of the same essence as the flesh, he will

be of two hypostaseis. If on the other hand ( ) the essence of the flesh is different from the essence of

the God Word, then how come Christ is not two natures?