For a full presentation of the case for converting the UK’s road signs to metric units, see UKMA’s publication, “Metric signs ahead”, which can be downloaded from this web page. On this web page, we trace the history of the Department for Transport’s (DfT’s) unwillingness to fall into line with Government policy on metrication.

The lack of significant progress on converting road signage in the UK to metric units is perhaps the most obvious and visible example of successive governments’ failure to carry through the changeover which was begun in 1965.

To quote the 1972 White Paper on Metrication:

Hansard, 1970, quoted in the White Paper on Metrication of the Department of Trade and Industry, 1972, paragraph 107

Since then, there has been little progress toward the objective of converting road signs. In 1989 the UK Government secured a derogation permitting the UK to “fix a date” for this conversion, but there was no indication of what that date might be nor even of when the date would be fixed. Indeed, in response to the publication of “Metric signs ahead” in 2006, the DfT made it clear that it had no plans to carry out its obligation, which a spokesperson described as “a waste of taxpayers’ money”.

In 2007, the DfT requested the European Commission to propose the complete removal of the obligation to fix a date for converting road signs to metric. The Commission duly obliged, partly on grounds of “subsidiarity”, and the resulting amendment to the Directive was finally agreed in 2009. Contrary to popular myth, there has never in fact been any pressure from the European Union for the UK to convert its road signs, and the amendment has made little practical difference.

Needless to say, this change in EU law, and the UK’s subsequent withdrawal from the EU in 2020, in no way detracts from the case for converting the UK’s road signs.

Speed limits

The metrication of speed limits had originally been announced in Parliament in 1969, with the changeover scheduled to happen in 1973.

Hansard, 5 March 1969

The announcement was widely reported in the following day’s newspapers. However, in 1970 all plans were postponed indefinitely. The Government published the following press release to accompany the announcement in Parliament:

No Speed Limit Metrication, 1970

Click image to access pdf

In November 1970, the Government had promised to produce a White Paper setting out the new administration’s policy on metrication. When this was finally published in February 1972, in order to avoid the embarassment of changing policy on speed limits yet again, the White Paper included the following statement:

However, the White Paper created a rod for the Government’s own back. In subsequent discussions on metrication, for the remainder of the administration’s term, it became the main reason why the changeover of speed limits could not begin until the late 1970s at the earliest.

The White Paper created a quandary for the Government which had also helped draft the 1971 EEC Directive on Units of Measurement committing the Government to switch all road signs to metric units by 1979. Government documents from the 1970s show that considerable effort was devoted to this politically-manufactured problem rather than dealing with the real task in hand, which should have been the planning of the metric changeover of the road signs themselves:

a) to adhere to the strict interpretation of October 1976 and try to convert all our signs by then;

b) to go to the Commission and try to persuade them 1979 is a reasonable interpretation, and if we can’t try to get an amending Directive, for 1979 or later;

c) to rely on the elements of doubt and plan for conversion by October 1979.

Course a) is I think out of the question, First on practical grounds we could possibly – at substantial extra cost – convert speed limits by 1976 but not more than a small proportion of the others (unless of course we mounted a crash programme at heavy cost and to the detriment of other things in the traffic and safety field).

Secondly, on political grounds it does not accord with the re-assurance to the public given in the White Paper that road signs will be left for several years.

Course b) is a possibility. My belief however is that once we put it to the Commission they will be bound to take a strict view and that will mean a fresh Directive. I do not think the importance of the point justifies asking Ministers to pilot one through – assuming the French etc. allowed us to. I.T. Division will no doubt have views here on how it fits into our current pattern of dealings with EEC.

Course c) is the one I would at this stage recommend. It does sufficient justice to the undertaking in the White Paper. On the other hand it does also expose us to challenge by the Commission, on the grounds that we are failing to comply with the Directive (or should have secured an adaption i.e.) but I think that is a risk we should be prepared to take. Our answer would be to make as much as we can of the legal doubts, to point out that the special problems of traffic signs had clearly not been envisaged in the preparation of the Directive, to stress that we had no intention of not fulfilling our obligations, it was merely a question of being a little behind in this one specialised field and that safety considerations as well as practical ones lead inevitably to 1979 as the shortest practical timescale.”

Metrication of Speed Limits and Traffic Signs, 9 January 1973

Click image to access pdf

A ministerial briefing note from the time included advice on how to answer any awkward questions that might be asked:

A. No date has yet been fixed but the Government have a completion date of 1979 in mind.

Q. Why not earlier?

A. This is a complex operation requiring several years for careful planning and efficient execution, integrated with the normal work of installing and maintaining road signs.

Q. Why not later?

A. Quite apart from EEC commitments, road signs cannot remain imperial in a metric world.

Q. Are we not committed to 1976 by EEC?

A. The Directive was not drafted with traffic control in mind; 1979 accords with its general intention and is in any event the earliest practicable date.

Metrication of Speed Limits and Road Signs

Click image to access pdf

Perversely, one of the reasons cited for not switching to metric units, after 1973, was the belief that many local authorities, that had previously been keen to switch to metric units, would now be hostile to the idea, following the Ministry of Transport preventing them from switching to metric units in the late 1960s, when all road signs were upgraded to Vienna Convention compliant “Warboys” signs:

Metrication of Speed Limits – Background Notes

Click image to access pdf

Arguments for and against the Metrication of Speed Limits

Ministry of Transport, 1969

Some of the Department for Transport’s early thoughts on the subject of metrication of speed limits are recorded in a Department document from 1969 that summarises arguments for and against the metrication of speed limits:

Arguments for and against the Metrication of Speed Limits, 1969

Click image to access pdf

| Ministry of Transport, 1969 | UKMA analysis |

| AGAINST | |

| “It can be argued that there would be a hostile public reaction to the cost and inconvenience of the proposed change on the grounds that considerable expenditure should not be incurred merely to alter the system which will not benefit motorists generally in this country.” | On the contrary, continuing to use a measurement system that the majority of motorists have not been taught in schools cannot possibly benefit motorists. |

| “Metric traffic signs would not help exports, nor do they relate to a tangible commodity where new measurements would rapidly become familiar by individual experience.” | Any relation of traffic signs to exports and tangible commodities is irrelevant. The argument that “new measurements would rapidly become familiar by individual experience” is actually an argument in favour of proceeding with the metrication process. |

| “Speed limits involve only a few numerals and are easier to understand but it can be argued that the conversion of directional and other signs should be delayed for several years in order to allow the public to get more experience of the metric system first.” | This argument never had any validity. Experience of the metric system comes with its use. Delaying the introduction of metric units on road signs denies any possibility of experiencing roads signed in metric units. Fifty years after the metric system became the primary system of measurement taught in schools, and fifty years after the introduction of food sold in metric packs, this argument is now completely bogus. |

| FOR | |

| “On the other hand it is fair to say that if metrication is to be adopted generally for its benefits in trade, commerce and education, it is difficult to justify any long term exception in the field of road traffic.” | More than fifty years later, there is no justification. |

| “In the long term this could only appear quite anomalous and confusing to a new generation brought up to think metric.” | This statement has proved to be prophetic. Fifty years after the metric system became the primary system of measurement taught in schools, and more than twenty years after imperial units ceased to be used for most other official purposes, the use of imperial units on road signs could not be any more anomalous and confusing. |

| “A public decision against metrication of traffic signs now might well be regarded as a breach in the Government’s metrication policy as a whole.” | The Government’s failure to metricate speed limits, and road signs in general, caused immense harm to the national metrication programme.

An early change to metric road signs, backed by an information campaign on a similar scale to that of the decimalisation of currency in 1971, would have ensured that the public were on board with the long-standing goal of having a single, rational system of measurement for all official purposes. Instead, the silence of successive governments on metrication left much of the public with the impression that metrication was in some way unpatriotic and something that the Government was only doing under pressure from foreign powers. If speed limits had switched to metric units in 1973 as originally planned, the metrication of the retail sector would most likely have been completed before 1980, rather than being dragged out until the end of the century. |

Height and width restriction signs

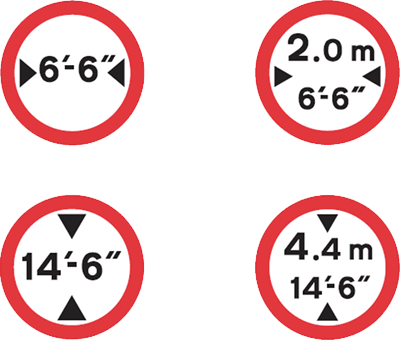

In September 2009, despite its implacable opposition to general metric conversion, the DfT proposed that within 4 years imperial-only height and width restriction signs (roundels) should no longer be permitted and should be replaced by dual metric/imperial signs. Similarly, imperial warning signs (red triangles) should only be used in conjunction with an accompanying metric sign (The difference between the rules for roundels and triangles is that the triangular shape prevents both metric and imperial units appearing on the same sign).

Some time after the 2010 general election, the DfT dropped plans to make metric units mandatory on restriction signs and to require imperial warning signs to be accompanied by metric warning signs. The regulations that made imperial units mandatory and metric units optional for warning and restriction signs remained unchanged until the TSRGD 2016 came into force on 22 April 2016. On that date, metric units became mandatory for all new height and width restriction signs.

When imperial-only roundel signs (left) are replaced, the dual metric/imperial roundel signs (right) must be used.

When imperial-only warning signs (left) are replaced, the dual metric/imperial warning signs (right) must be used.

Although this move was welcome as far as it went, the DfT had made it clear that it was “a specific solution to a specific problem” (i.e. disproportionate numbers of bridge strikes by foreign lorries) and was not part of any long-term conversion plan. It should also be pointed out that the UN-sponsored Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals (an international treaty to which the UK is a signatory) specifies exclusively metres on height, width and length restriction signs.

DfT objections to metric conversion

The DfT’s objections to conversion are longstanding but have changed over the years. The original postponement of the 1973 target was clearly the result of a successful campaign by politicians opposed to metrication generally, but the then Minister was careful not to rule out conversion at some time in the future, and the 1972 White Paper commented that, “The change of speed and distance signs to metric units will need to be considered in detail, but not for some years.”

Since then, the objections have been, variously, that

| Department for Transport | UKMA analysis |

| “Drivers who have not received metric education at school would be confused by a change to metric units.” (Parliamentary Written Answer, 11 July 2002, Hansard, Col 1116w) Subsequently, it was suggested that conversion might be considered when a majority of drivers had received metric education. |

This point has almost certainly already been reached. This is because metric units have been mandatory in state schools since 1974, and therefore all drivers who were born after 1964 will have received their secondary education using metric units. In any case, evidence from other countries’ changeovers demonstrates that such “confusion” is not a significant problem. |

| “Dual signage (i.e. metric and imperial on the same or adjacent signs) would be confusing – and therefore dangerous in a safety-critical environment.” (quoted from a letter from the Permanent Secretary, 2003) |

However, distance signage is not “safety-critical”; speed limits would obviously NOT be dual signed; and the DfT already authorises dual units on height and width restriction signs – which ARE “safety-critical”. |

| As the two previous arguments had lost any validity they might have had, in 2006 the DfT produced a new argument: Cost.

They claimed that the cost of conversion, estimated at £680 – 760 million (ca. £1400/sign) would be disproportionate to the benefits for transport and is not a priority for scarce resources. |

With regard to the costs argument, several points should be made:

|

This failure to even begin to plan for metric conversion of road signage is particularly serious and indeed wasteful since, if such a plan existed, any new imperial signage could be installed in a way that minimised future conversion costs. An example of the DfT’s wasteful approach is the installation on motorways of electronic variable speed limit signs that are not capable (without amendment) of showing the three digits that could be needed to display higher speed limits (e.g. 100 km/h).

This variable speed limit sign cannot accommodate more than two digits without modification – hence can only show speed limits up to 90 km/h

Even worse are the LED speed limit signs activated by drivers, which are not capable of amendment, as in the example above.

UKMA therefore calls upon the UK Government without further delay to announce the date when the UK’s road signage (and hence speed limits) will be converted to metric units. (This date should be as soon as reasonably possible, taking into account the time required to pass the necessary legislation and physically replace or amend the imperial signage. Based on other countries’ experience, it is believed that this date could be within three to five years of the announcement.

As indicated above, UKMA considers that the conversion of distance signage could (as in Ireland) be spread over an extended time period, but we do not favour a long transitional period during which both imperial and metric signs are in place. We are particularly opposed to the erection of new distance signs displaying both units on the same sign as we feel that such signs would become permanent and drivers would have no incentive to adjust to metric units. Whether the changeover should be by totally new signs or by amending existing signs is a matter for detailed consideration.

The changeover arrangements should also include the use of the correct international symbols, including “km/h” to denote “kilometres per hour”. In particular, the erection of further signs giving “m” as an abbreviation for “mile” should be prohibited with immediate effect.

The changeover programme will also need to include legislation to revise speed limits, revision of various Regulations, including the Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions (TSRGD) and the Road Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations to require legible “km/h” on speedometers, together with an intensive campaign of driver education shortly before and during the changeover.